Microbialites of Bridger Bay, Antelope Island, Great Salt Lake

by Stephanie Carney and Michael D. Vanden Berg

GGreat Salt Lake (GSL) in northern Utah has a perception problem. Visitors often comment on the stinking “gross” lake that should be avoided, unless you enjoy swarms of biting gnats and being surrounded by millions of brine flies. However, those of us that live in Salt Lake City know the truth; GSL is an unsung gem, full of life and beauty. But our secret is getting out, especially over the past few months as historic low lake level has brought renewed attention to the lake. GSL is one of the most important habitats for migratory birds in western North America, supporting upwards of 5 million shorebirds, almost 2 million eared grebes, and hundreds of thousands of waterfowl during spring and fall migrations. The migratory birds take advantage of GSL’s unique ecosystem and extensively feed on the lake’s brine shrimp and brine flies. However, none of this biodiversity would be possible without the vastly underappreciated base of the GSL ecosystem—the abundant and diverse algae and bacteria. The bacterial community is particularly intriguing, forming remarkable microbial mats that cover and help create unique, organic sedimentary rocks called microbialites. And Bridger Bay on the northwest corner of Antelope Island is the perfect place to view them.

Microbialites mostly form in saline lakes or restricted ocean settings but can also form in specific freshwater conditions. They form as a result of microbial mats trapping and binding sediments, like ooids, pellets, and carbonate grains. The mats also facilitate the precipitation of minerals, most commonly calcium carbonate (limestone), through photosynthetic processes that introduce oxygen to the water. The microbialites grow slowly as more sediment and precipitated calcium carbonate accumulate. Microbialites have been forming on Earth for billions of years and can be found worldwide in the fossil record. Australia boasts the oldest fossilized microbialites (3.5 billion years old), which are the first evidence of life on Earth. In fact, researchers believe that microbial communities that built the first microbialites likely contributed much of the oxygen to Earth’s early developing atmosphere. “Modern” microbialites, those that formed during the Holocene Epoch (between about 12,000 years ago and the present), are rarer than the abundant examples found in the fossil record. The most famous recent examples are stromatolites, an internally layered type of microbialite, found in Hamelin Pool of Shark Bay in the shallow coastal waters of western Australia. However, to the surprise of many, our very own GSL hosts the largest population of Holocene microbialites in the world.

The shallow, saline, nearshore environment around GSL is an ideal place for the development of microbialites. Cyanobacteria are the main microbes responsible for microbialite growth in GSL and form thin, dark green-brown mats that cover the domal structures. However, this microbial mat is only active on microbialites found in the south arm of GSL. After the construction of the earthen railroad causeway in 1959, the north arm water turned hypersaline and the microbial mat communities could not survive, leaving behind only remnant, desiccated, salt-encrusted mounds. If microbialites are still “growing” today, this growth is only occurring in the south arm and would be directly associated with the living microbial mats. One of the most accessible places to see these amazing structures covered with a healthy microbial mat is at Bridger Bay.

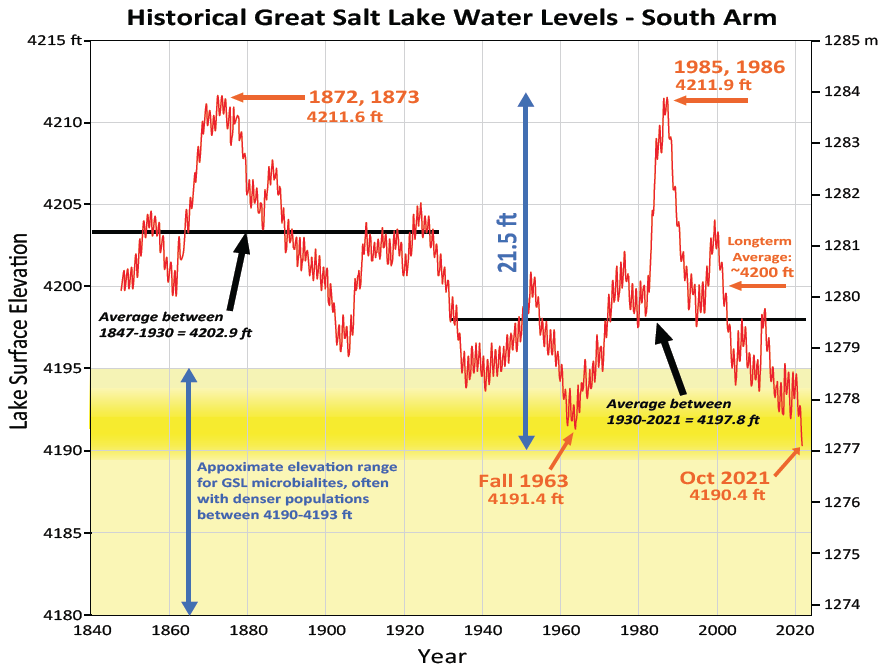

However, at the time of this writing, the living microbialites in the south arm of GSL are in danger. Because microbialites thrive in an extensive shallow-shelf environment, they are at the mercy of the ever-changing lake level. Drought and the ever-increasing demands of water along the Wasatch Front have caused GSL to drop to its lowest level in more than 150 years of recorded lake history. In October 2021, the lake elevation reached a low of 4,190.2 feet (compared to the long-term, historically recorded average of about 4,200 feet), well below the previous historic low of 4,191.4 feet recorded in 1963. The GSL microbialites occupy elevations ranging from about 4,195 to roughly 4,180 feet, but the densest populations often occur between 4,192 and 4,191 feet. Therefore, the recent extreme low lake levels have exposed a significant proportion of the microbialite population in the south arm. Studies have shown

that it only takes a short period of exposure time, maybe weeks, for the microbial mat to die and erode off the top of the microbialite structures, but it takes several years of higher lake level before the microbial mat can potentially recover. The exposure during fall 2021 will likely have lasting, unpredictable consequences for the microbialite population and the base of GSL’s ecological pyramid for years to come, even if lake levels return to higher levels in subsequent years.

The recent exposure of these unique structures has highlighted the distressful situation at GSL. The Utah Geological Survey (UGS) along with several other dedicated researchers will continue to monitor and study the microbialites and their relationship to the greater GSL ecosystem. If you would like to see these amazing microbialite structures firsthand (without having to swim in 10 feet of water), Bridger Bay on Antelope Island offers the most convenient location. We ask that visitors DO NOT walk on these delicate structures. They easily break apart under the weight of a person, and what took hundreds of years to build can be ruined with one errant step. We hope that if lake levels return to more normal elevations, the microbial mat can recolonize these structures and the GSL ecosystem can be renewed. For more information, please see our web page at https://geology.utah.gov/energy-minerals/hydrocarbons/microbialites/.