Great Salt Lake’s Gunnison and Cub Islands Come into Focus

by Donald L. Clark (UGS Geologic Mapping Program) and Bonnie K. Baxter (Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster College)

Location, Setting, and Mapping

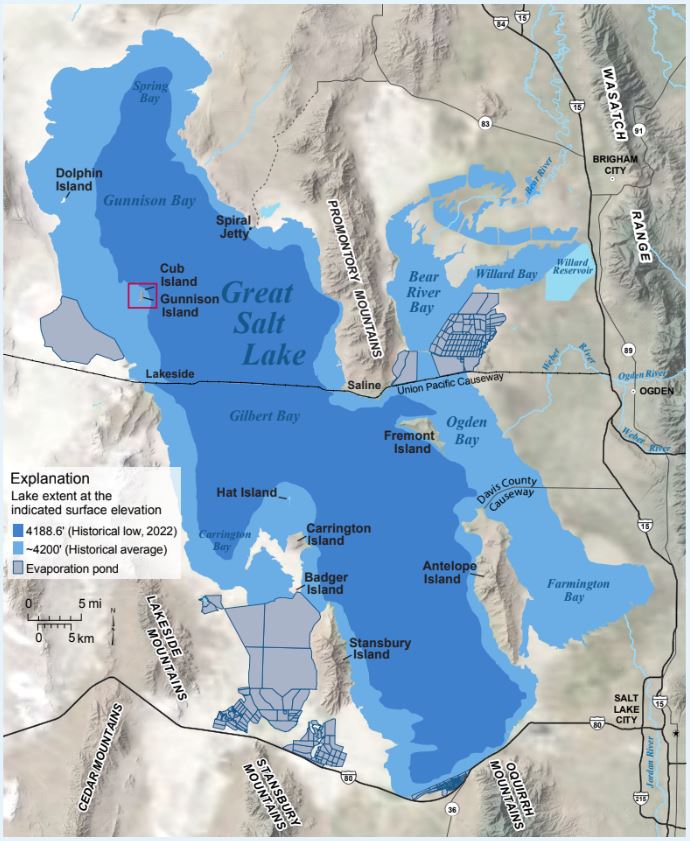

Overview map of Great Salt Lake and surrounding area. The map depicts Great Salt Lake at the historical average elevation of about 4200 feet (1280 m) and the new historical low of 4188 feet (1277 m). Red box shows location of Gunnison and Cub Islands.

The islands of Great Salt Lake (see Survey Notes, 2010, v. 42, no. 2) provide glimpses into the geology as well as the scenic and biologic diversity of the lake’s basin. Gunnison Island and its smaller neighbor Cub Island are located near the west shore of Great Salt Lake in the part of the lake’s north arm called Gunnison Bay. The north arm is currently cut off from freshwater inputs by a railroad causeway and is thus the saltiest part of the lake, almost ten times the salt content of the world’s oceans. The islands are a surreal landscape of low rocky ridges with sweeping sandy and gravelly beaches currently flanked to the east and north by an expanse of pink waters, blowing white foam, and miles of mudflats on the west dotted with remnant carbonate mounds (microbialites).

Both islands (roughly one mile long and one-half mile wide) are a designated State Wildlife Management Area that is strictly off-limits to public access. However, during 2020–21 the Utah Geological Survey (UGS) had the rare opportunity to accompany scientists with the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (UDWR) and Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster College (GSLI) to visit Gunnison and Cub Islands. We were able to conduct geologic mapping on the islands as part of our continued effort to map the geology of the entire state at an intermediate scale. To prevent disturbance to the resident pelicans of the island, we completed our fieldwork after the birds had migrated and before their return.

American white pelicans and California gulls at central Gunnison Island. Photo from Gunnison Island PELIcams, courtesy of Utah Division of Wildlife Resources–Great Salt Lake Ecosystem Project and Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster College, 2019.

Biological and Historical Significance

When surveying the lake in the early 1850s, Captain Howard Stansbury, of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, and his crew visited Gunnison Island and recorded notes and drawings regarding the pelicans who were breeding there. Today we know that this rookery is one of the largest breeding colonies of American white pelicans in North America. GSLI and UDWR have monitored the pelicans using trail cameras since 2016, providing insight into the unusual behavior of fish-eating birds that nest in a location having no available on-site food.

In addition to remarkable wildlife, Gunnison Island is host to several important historical sites including Stansbury’s topographic survey triangulation station, still located on the high point at the north end of the island. Foundational remnants (cemented-gravel slabs) where the artist and writer, Alfred Lambourne, spent a year (1895–96) also remain visible. Other sites of human activity include a former guano (bird excrement used for fertilizer) collection area on the east beach.

Geology

The geology of the islands was previously known only through regional geologic mapping (W.L. Stokes in 1963 and H.H. Doelling in 1980). The 2020–21 geologic reevaluation found an ascending section of Upper Cambrian-, Ordovician- and Silurian-age dolomite and limestone bedrock that ranges from about 500 to 430 million years old. These rocks formed during part of a period of long-lived marine conditions when western Utah sat along a passive continental margin. Later, northern Utah was broken into a series of large sheets of rock that moved several miles along low-angle, east-directed thrust faults during the Sevier orogenic mountain building event, about 150 to 50 million years ago. Due to limited bedrock exposures in the vicinity, it is uncertain which thrust sheet the islands are located on. In spite of this uncertainty, the subsurface geology east of the islands was investigated most recently from 1978 to 1980 for the Rozel oil field (see Survey Notes, 1995, v. 27, no. 3). A large northwest-trending fault bisects Gunnison Island, cutting out a section of Ordovician strata including the Kanosh Shale. Cub Island has more exposed limestone, yet microfossils there indicate the limestone is correlative to rocks at the north end of Gunnison Island. Geophysical gravity data show that the islands lie on an uplifted bedrock block (horst) that projects northward from Strongs Knob and the northern Lakeside Mountains. This part of Utah was broken into a series of mountains/hills (horsts) and basins (grabens) over the last 20 million years. The islands’ rocky core is flanked by loose and cemented gravel and oolitic sand comprising the beach deposits that formed during the rising and falling of Great Salt Lake waters over the past 13,000 years. Surrounding the islands are fields of modern microbialites (see Survey Notes, 2022, v. 54, no. 1), rocky structures built by photosynthesizing microorganisms that once powered the lake’s ecosystem, but they are now vestiges due to the high salt content of the north arm waters. The results of this mapping are shown on the interim geologic map of the southwestern part of the Promontory Point 30’ x 60’ quadrangle (UGS Open-File Report 739).

A Fluctuating Great Salt Lake

Great Salt Lake is a terminal lake at the very bottom of the watershed, like the bottom of a bathtub, that rises and falls in elevation in response to varying precipitation and evaporation. Over the past 13,000 years the lake elevation has fluctuated between about 4,250 and 4,170 feet (1,295–1,271 m) above sea level, but the timing of specific rises and falls is not well documented due to limited sediment and landform information. One substantial rise to 4,250 feet (1,295 m) about 12,000 years ago is called the Gilbert episode. Since the lake elevation has been measured starting in the mid-19th century, scientists have recorded a historical average of 4,200 feet (1,280 m). The lake recently went from a historic low level in 1963 of 4,191 feet (1,278 m) to a historic high of 4,212 feet (1,284 m) in 1986–87, but has since declined to a new historic low currently near 4,188 feet (1,277 m). The new low follows a century of water diversions for consumptive uses, coupled with the ongoing drought and changing climate.

Impacts of the water-level decline on the Great Salt Lake ecosystem are being monitored in the south arm of the lake, which is less saline than the north arm and hosts a food web including brine shrimp, brine flies, and many of the ten million birds hosted at Great Salt Lake and its surrounding wetlands that eat them. This biology is absent from the saltier north arm where the rose-colored brine present near Gunnison and Cub Islands is due to microorganisms. However, lower water levels have led to the formation of landbridges to the islands, allowing predators such as coyote and fox access to the nesting pelicans, as well as exposing mudflats and playa, which could source dust storms as well as small-particle and heavy-metal pollution, impacting human health.

Future projections for Great Salt Lake remain dire with decreased inflows. In 2022, the Utah State Legislature recognized the importance of our “inland sea,” and passed several bills to address the issue of getting water to the lake. They also appropriated $40 million to fund a water trust to address lake issues (Utah House Bill 410).

Our geologic mapping and collaborative work are part of the science undertaken to understand the complex composition of Great Salt Lake and its environs. This work shows that Gunnison and Cub Islands are an integral part of a fluctuating Great Salt Lake, and in turn, a multifaceted asset of the State of Utah.