Major John Wesley Powell’s 1869 Journey Down the Green and Colorado Rivers of Utah

by Thomas C. Chidsey, Jr.

Past these towering monuments, past these mounded billows of orange sandstone, past these oak-set glens, past these fern-decked alcoves, past these mural curves, we glide hour after hour, stopping now and then, as our attention is arrested by some new wonder…

These words by Major John Wesley Powell, August 3, 1869, describe the scene as he and his comrades floated along the Colorado River in what is now southern Utah. Anyone who now travels his same route or visits the various national parks and surrounding regions likewise has their “attention arrested by some new wonder!” Powell is best known for his historic journey down the Colorado River through the depths of the Grand Canyon 150 years ago. However, of that 1,000-mile journey, about 570 miles (roughly 58 percent) were down the Green and Colorado Rivers through Utah. Most of the spectacular areas and landmarks along the way that are so familiar to generations of Utah citizens and visitors were named by Powell and his party.

The purpose of Powell’s 1869 expedition was to survey the geology, geography, and water resource potential for settling the region, and document ethnography and natural history of the canyons of the Green and Colorado Rivers. Though his expedition was “scientific,” Powell was well aware that he was competing with other government surveys for funds, and that adventures such as his river journey drew much public interest and support. The expedition was made possible, in part, by the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad (Union Pacific) through Wyoming, which delivered four modified, round-bottomed Whitehall rowboats that were built in Chicago: Maid of the Cañon, Kitty Clyde’s Sister, No Name, and the Emma Dean named after Powell’s wife and specially rigged for him to command during the trip to accommodate him having one arm.

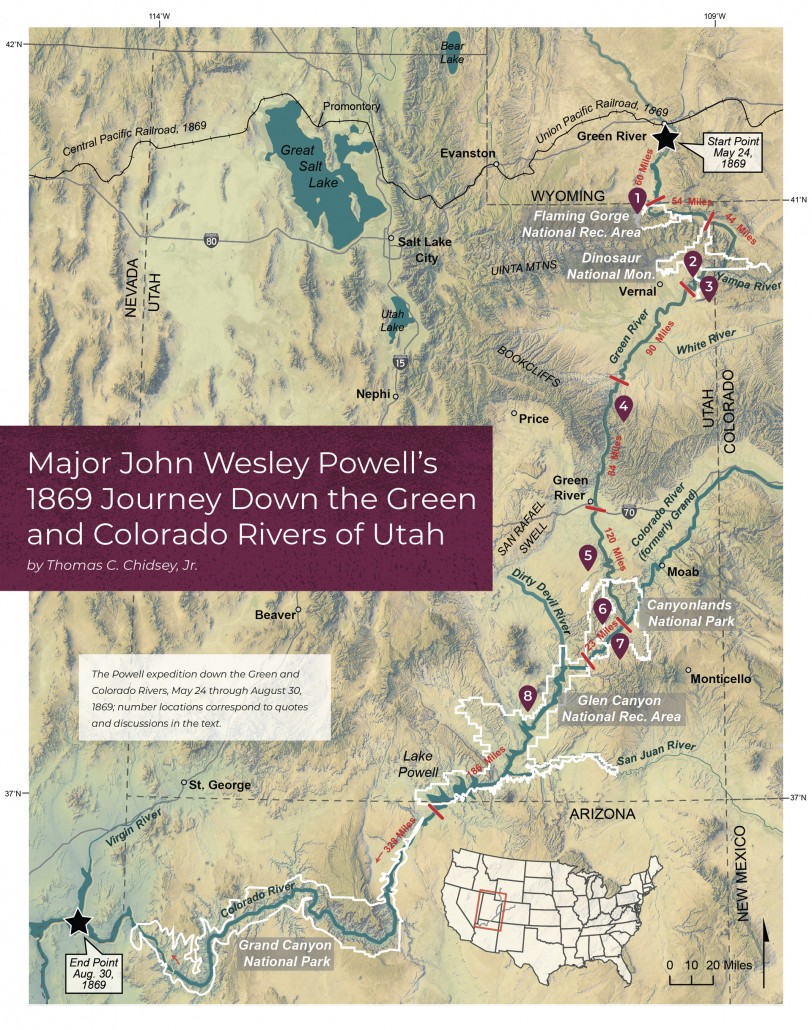

Powell and his party of nine others departed Green River Station (now the town of Green River, Wyoming) on May 24, 1869, two weeks after the Golden Spike had been laid at Promontory, Utah, completing the Transcontinental Railroad. The boats were laden with supplies to last 10 months and they took several scientific instruments including sextants, chronometers, thermometers, compasses, and barometers (to measure the altitude of the river and surrounding terrain). They would endure numerous hardships along the way including negotiating hundreds of rapids, the loss of two boats with much of their supplies and scientific instruments, surviving near drownings, food spoilage and near starvation, and even outrunning a flash flood. One member of the crew would depart the expedition near Vernal, Utah, having had enough adventure, and three others left near the journey’s end thinking an impending rapid too dangerous—they were never seen again.

MAP POINT 1

Traveling uneventfully down 60 miles on the Green River, most of which is now Flaming Gorge Reservoir, Powell and his party reached the Utah Territory on May 26.

The river is running to the south; the mountains have an easterly and westerly trend directly athwart its course, yet it glides on in a quiet way as if it thought a mountain range no formidable obstruction. It enters the range by a flaring, brilliant red gorge, that may be seen from the north a score of miles away. The great mass of the mountain ridge through which the gorge is cut is composed of bright vermilion rocks; but they are surmounted by broad bands of mottled buff and gray, and these bands come down with a gentle curve to the water’s edge on the nearer slope of the mountain. This is the head of the first of the canyons we are about to explore—an introductory one to a series made by the river through this range. We name it Flaming Gorge [1 on map].

Major John Wesley Powell,

May 26, 1869

The mountain range Powell describes is the east-west-trending Uinta Mountains. The rocks at the entrance to Flaming Gorge that so much impressed Powell are the north-dipping, slope-forming, vermilion-colored Triassic (251 to 200 million years ago [Ma]) Moenkopi and Chinle Formations overlain by the buff-gray Triassic-Jurassic (200 to 183 Ma) Nugget Sandstone and the Jurassic (169 to 155 Ma) Carmel, Entrada, and Stump Formations.

MAP POINT 2

After crossing the Uinta fault, the Green River follows a generally easterly course through Precambrian (800 to 770 Ma) rocks exposed spectacularly in Red Canyon (now popular for river rafting below the Flaming Gorge Dam) and then Browns Park. Eventually (after about 54 miles), the river enters Colorado through the Gates of the Lodore and turns south into a region that is now part of Dinosaur National Monument where Powell lost the No Name, much of their supplies, and scientific instruments in a rapid they appropriately named Disaster Falls. After the river course changes to the west, it reenters Utah.

The Green is greatly increased by the Yampa [River], and we now have a much larger river. All this volume of water, confined, as it is, in a narrow channel and rushing with great velocity, is set eddying and spinning in whirlpools by projecting rocks and short curves, and the waters waltz their way through the canyon, making their own rippling, rushing, roaring music…One, two, three, four miles we go, rearing and plunging with the waves, until we wheel to the right into a beautiful park and land on an island, where we go into camp…e broad, deep river meanders through the park, interrupted by many wooded islands; so I name it Island Park, and decide to call the canyon above, Whirlpool Canyon [2 on map].

Major John Wesley Powell,

June 21 and 22, 1869

The oldest formation exposed in Whirlpool Canyon is the Precambrian (900 Ma) Uinta Mountain Group which is overlain by Cambrian (540 Ma) Lodore Sandstone and Mississippian and Permian (340 to 275 Ma) strata, all relatively resistant to erosion and deeply incised by the river. When Powell exited the canyon and entered the open area he named Island Park, the expedition had crossed the northeast-southwest-trending Island Park fault. This major fault displaces softer, less-resistant Triassic and Jurassic formations on the west side, including the Moenkopi and Chinle Formations exposed in Flaming Gorge, against the Pennsylvanian-Permian (280 to 275 Ma) Weber Sandstone on the east side.

MAP POINT 3

At the lower end of the park, the river turns again to the southeast and cuts into the mountain to its center and then makes a detour to the southwest, splitting the mountain ridge for a distance of six miles nearly to its foot, and then turns out of it to the left. All this we can see where we stand on the summit of Mount Hawkins, and so we name the gorge below, Split Mountain Canyon [3 on map].

Major John Wesley Powell,

June 24, 1869

For the description of Split Mountain Canyon, see the “Glad You Asked” article in this issue.

MAP POINT 4

After passing through Split Mountain, the Green River follows a gentle, south-southwesterly meandering course through the Eocene (55 to 43 Ma) Uinta and Green River Formations in the Uinta Basin. Powell passed many major oil and gas fields that would not be drilled for many years. After about 90 miles the river again downcuts into older rocks which created another major and perilous canyon for the Powell expedition.

After dinner we pass through a region of the wildest desolation. The canyon is very tortuous, the river very rapid, and many lateral canyons enter on either side. These usually have their branches, so that the region is cut into a wilderness of gray and brown cliffs. In several places these lateral canyons are separated from one another only by narrow walls, often hundreds of feet high—so narrow in places that where softer rocks are found below they have crumbled away … Piles of broken rock lie against these walls; crags and tower-shaped peaks are seen everywhere, and away above them, long lines of broken cliffs; and above and beyond the cliffs are pine forests, of which we obtain occasional glimpses as we look up through a vista of rocks. The walls are almost without vegetation; a few dwarf bushes are seen here and there clinging to the rocks, and cedars grow from the crevices—not like the cedars of a land refreshed with rains, great cones bedecked with spray, but ugly clumps, like war clubs beset with spines. We are minded to call this the Canyon of Desolation [4 on map].

Major John Wesley Powell,

July 8, 1869

Desolation Canyon exposes rocks of the Eocene (55 to 45 Ma) Green River and Paleocene-Eocene (about 60 to 55 Ma) Wasatch Formations which, in this area, were deposited as shallow-water muds, shoreline river deltas, and alluvial plains along or near the southern parts of an ancient lake called Lake Uinta. The Green River and Wasatch Formations are major producers of oil and gas in the Uinta Basin.

Again, the large rapids in Desolation Canyon posed major difficulties for Powell and his party. Most of the rapids that they encountered here and along the entire journey formed adjacent to major side canyons when large flash floods deposited boulders in the rivers. These boulders dammed up the rivers (a calm before the storm!) with the rapid created where the water flows over the “dam.”

MAP POINT 5

The Green River continues to follow a southerly course into Gray Canyon, cutting down through the coal-bearing formations of the Cretaceous (84 to 67 Ma) Mesaverde Group until it exits the canyon at the Book Cliffs near the town of Green River, Utah. From there the river continues south, eroding deeper into older strata that create the classic Colorado Plateau canyon country of southern Utah.

…with quiet water, still compelled to row in order to make fair progress. The canyon is yet very tortuous. About six miles below noon camp we go around a great bend to the right, five miles in length, and come back to a point within a quarter of a mile of where we started…There is an exquisite charm in our ride to-day down this beautiful canyon. It gradually grows deeper with every mile of travel; the walls are symmetrically curved and grandly arched, of a beautiful color, and reflected in the quiet waters in many places so as almost to deceive the eye and suggest to the beholder the thought that he is looking into profound depths. We are all in fine spirits and feel very gay, and the badinage of the men is echoed from wall to wall. Now and then we whistle or shout or discharge a pistol, to listen to the reverberations among the cliffs… we name this Labyrinth Canyon

[5 on map].Major John Wesley Powell,

July 15, 1869

The Green River meanders through Labyrinth Canyon exposing spectacular sandstone cliffs of the Triassic-Jurassic Glen Canyon Group (see cover image). These strata were deposited in great “seas” of wind-blown sand like those of the modern Sahara, separated by a period when the climate changed and westerly flowing, sand-laden braided streams dominated the region.

The Colorado Plateau began rising during the Miocene Epoch (23 Ma). At that time the ancestral Green River and its tributaries flowed through meandering channels in wide valleys on easily eroded rocks such as the now-removed Cretaceous Mancos Shale, still exposed just south of the Book Cliffs. Once these river channels were established, they later became superimposed and entrenched into resistant rocks, such as the sandstones of the Glen Canyon Group, as the landscape changed from one of deposition to one of massive erosion where thousands of feet of sedimentary rocks have been removed.

MAP POINT 6

From Labyrinth Canyon the river continues a similar meandering course, cutting into even older rocks, and enters what is now Canyonlands National Park.

The stream is still quiet, and we glide along through a strange, weird, grand region. The landscape everywhere, away from the river, is of rock—cliffs of rock, tables of rock, plateaus of rock, terraces of rock, crags of rock—ten thousand strangely carved forms; rocks everywhere, and no vegetation, no soil, no sand. In long, gentle curves the river winds about these rocks… rapid running brings us to the junction of the Grand [now the Colorado River] and Green, the foot of Stillwater Canyon, as we have named it [6 on map]. These streams unite in solemn depths, more than 1,200 feet below the general surface of the country.

Major John Wesley Powell,

July 17, 1869

The rocks Powell described from Stillwater Canyon consist of Triassic Moenkopi and Chinle Formations that he first observed in Flaming Gorge, and the Permian (280 to 275 Ma) Cutler Group. The chocolate- to brown-red-colored Moenkopi was deposited in a tidal-flat environment, as attested by its abundance of ripple marks on thin slabs of rocks, and the Chinle, famous for its petrified wood, uranium, and beautiful multicolored mudstone and shale, represents a river floodplain. The Permian Cutler Group consists of the red-brown floodplain deposits of the Organ Rock Formation at river level capped by prominent cliffs of the White Rim Sandstone which represents ancient coastal dunes.

Large uplifts and basins developed in the Colorado Plateau during the Laramide orogeny (mountain-building event) between the latest Cretaceous (about 70 Ma) and the Eocene (about 34 Ma). Canyonlands National Park and the surrounding region is on the northern end of the broad Laramide-age Monument uplift, which is responsible for exposing the impressive stratigraphic section of older rocks carved into by both the Green and Colorado Rivers in southern Utah.

MAP POINT 7

Once past the confluence of the two great rivers, the Colorado River flows in a southwesterly direction descending through one of the wildest series of rapids in Utah until it reaches Lake Powell 23 miles downstream.

We come at once to difficult rapids and falls, that in many places are more abrupt than in any of the canyons through which we have passed, and we decide to name this Cataract Canyon [7 on map].

Major John Wesley Powell,

July 23, 1869

The geology along Cataract Canyon is unique and the Colorado River likely has been a factor in the canyon’s structural development. The river follows a relatively straight course down the axis of a large anticline (upwarp) called the Meander anticline. Open-marine limestone beds of the Pennsylvanian (305 to 300 Ma) Honaker Trail Formation dip to the southeast and northwest, respectively, on each side of the river topped by progressively younger Permian formations. The Honaker Trail is underlain in the subsurface by the older Pennsylvanian Paradox Formation that contains evaporite rocks (gypsum and salt) which were deposited in a restricted marine environment. When under pressure, evaporites can flow like toothpaste being squeezed from a tube and push up the overlying rocks or even reach the surface (Powell recognized one such location and named it Gypsum Canyon, a side canyon to Cataract). The Meander anticline was formed this way and is underlain by a mass of mobilized gypsum and salt. As the Colorado River eroded the overlying section of rocks, the pressure on the evaporites below was reduced allowing them to push up even more. The evaporites withdrew from under the rocks adjacent to the canyon which caused collapse, faulting, and slumping towards the river. This process is still active today and contributes to huge rapids like Satan’s Gut and Little Niagara. This area is known as The Grabens in Canyonlands National Park.

MAP POINT 8

Upon leaving Cataract Canyon, the Colorado River turns westerly and enters the upper reaches of Lake Powell, named, of course, for the famous explorer. After passing the Dirty Devil River, so-called by one of Powell’s men because of its muddy water and foul smell, the rocks become younger in age (Permian, Triassic, and finally Jurassic) to the south.

On the walls, and back many miles into the country, numbers of monument-shaped buttes are observed. So we have a curious ensemble of wonderful features—carved walls, royal arches, glens, alcove gulches, mounds, and monuments. From which of these features shall we select a name? We decide to call it Glen Canyon [8 on map].

Major John Wesley Powell,

August 3, 1869

The features Powell used to name Glen Canyon are most prominently displayed in the Jurassic (190 Ma) Navajo Sandstone, famous for its classic cross-bedding and representing ancient dunes of windblown sand.

Glen Canyon and the canyons in the surrounding region, including those that Powell explored, formed within the past 5 million years by vigorous downcutting of the Colorado River and its tributaries, exposing more than 8,000 feet of bedrock that spans a period of about 300 million years. Powell no doubt would be shocked and amazed to see the reservoir that bears his name. All outcrops at river level and in many of the side canyons that Powell explored are covered by water, in many places hundreds of feet deep. Fortunately, the lake level creates an ideal horizontal datum along which large folds (anticlines and synclines) bring most of those outcrops, ranging in age from Triassic to Jurassic in the heart of Glen Canyon, to places where they can be observed from the comfort of a boat.

The 710-foot-high Glen Canyon Dam, located just south of the Utah border near Page, Arizona, was authorized by Congress in 1956 to provide water storage in the upper Colorado River basin, and construction began that same year. Lake Powell is the second largest reservoir in the United States (Lake Mead in Nevada and Arizona is the largest). The lake is 186 miles long, and with 96 major side canyons, it has more than 1,960 miles of shoreline—more than twice the length of the California coastline. The surface area of Lake Powell is 266 square miles and it is 560 feet deep at the dam. Lake Powell holds up to 27 million acre-feet of water, enough to cover the state of Ohio with one foot of water! The hot arid climate causes an average annual evaporation of 2.6 percent of the lake’s volume. Siltation in the lake averages 37,000 acre-feet per year, brought in principally from the San Juan and Colorado Rivers. That is the equivalent of 6 million dump trucks of silt each year! Even at that rate, it will take 730 years to fill the lake with silt.

Although the most famous part of Major John Wesley Powell’s 1869 expedition was the journey of what Powell called “the Great Unknown” of the Grand Canyon, he first spent most of his time exploring the canyons of the Green and Colorado Rivers in Utah. This expedition represents an amazing feat by Powell and his team at that time. Before Powell left the Utah Territory and entered what is now Arizona, he wrote “…we reach[ed] a point which is historic.” Powell was referring to a point along the Colorado River known as El Vado de los Padres or Crossing of the Fathers, a ford (now under 400 feet of water in Padre Bay in Lake Powell) named for Fathers Dominguez and Escalante who discovered it during their 1776 expedition through the region. For those of us who boat around Lake Powell or Flaming Gorge Reservoir, or raft the Colorado or Green Rivers, we too reach points that are truly historic—first named and described by Powell and his colleagues 150 years ago. Major John Wesley Powell’s expedition was truly a major contribution to science and an incredible adventure that still inspires a spirit of curiosity and sense of wonderment today.

Powell quotes from Canyons of the Colorado, by J.W. Powell, 1895.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tom Chidsey

is a senior scientist in the Energy & Minerals Program He has worked for the Utah Geological Survey for 30 years primarily conducting petroleum geologic studies. Tom is not only passionate about the geology of Utah, but history as well—especially the Civil War, World War I, and Major John Wesley Powell’s 1869 journey down the Green and Colorado Rivers He has retraced more than 800 miles of Powell’s route by raft and boat In addition, Tom was the senior author of the Utah Geological Association’s 2012 guide to the geology of Lake Powell.