Paleo News: New Discoveries of Morrison Formation Plant Fossils Expand Our Knowledge of Jurassic Ecosystems

by James Kirkland, Utah Geological Survey

John Foster, Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum

Don DeBlieux, Utah Geological Survey

ReBecca Hunt-Foster, Dinosaur National Monument

A few of the species from the Jurassic Salad Bar site. A) The reproductive organs of the fern Coniopteris hymenophylloides. B) Partial leaf of the ginkgophyte Sphenobaiera sp. C) Leaf bundles of the ginkgophyte Czekanowskia turneri. D) Partial leaf of the ginkgophyte Ginkgoites sp. E) Partial frond of the fern Coniopteris hymenophylloides. F) Abdominal segments and forewing of the giant water bug-like insect Morrisonnepa jurassica (Lara and others, 2020); abbreviation se = abdominal segment. G) Conchostracans, often called clam shrimp. All scale bars = 1 cm. Photos by Tom Howells, Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum.

Utah’s Jurassic-age Morrison Formation is world-famous for its many dinosaur fossil sites such as Dinosaur National Monument, Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, and the Hanksville-Burpee site. These sites attract visitors and researchers from all over the globe to see and study iconic dinosaurs such as Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, and Diplodocus among many others. Artistic museum reconstructions of these animals in their environment allow us to envision what it was like to be living in the distant past. These reconstructions are based on renderings of the plants that were living during the time of these dinosaurs. However, our knowledge of the plant communities that existed during the time of deposition of the Morrison Formation is limited because well-preserved plant fossils are quite rare. The discovery of a new fossil site in the Morrison Formation near Blanding, Utah, however, is greatly expanding our understanding of Utah’s environment during the Jurassic.

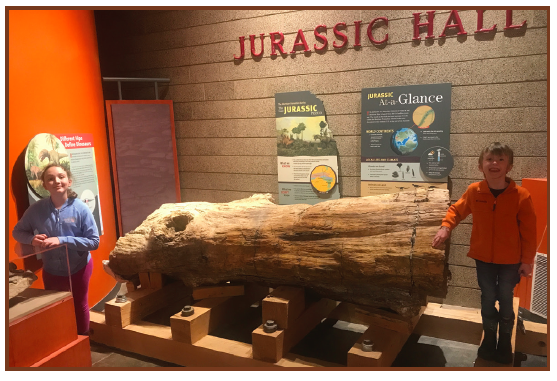

The most commonly preserved plant fossils in the Morrison are petrified conifer logs like those displayed at Escalante Petrified Forest State Park in south-central Utah. In 2015, the Utah Geological Survey (UGS) Paleontology Section helped move a large petrified log to a display near the park entrance, which allows visitors, especially those with limited mobility, to view the iconic fossils for which the park is named. Another extensive petrified forest in the Morrison Formation is located south of Dinosaur National Monument. The Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum (FHPR) in Vernal, Utah, led by Mary Beth Bennis and with the help of Utah Friends of Paleontology volunteers, collected a large petrified log from this area. This massive log, known as the “Manwell Log,” is on display at the Field House’s Jurassic Hall. Most of these Morrison Formation logs are from conifer trees and we sometimes find fossilized seeds and cones. Other less-common petrified woods include those of cycads, cycadeoids (an extinct group of cycad-like plants), and the stems of the enigmatic gymnosperm Hermatophyton.

The Manwell Log on exhibit at the Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum (Vernal) with Ruby and Harrison Foster for scale. The log preserves wood grain and bark textures. Photo courtesy of John Foster.

Sites that preserve identifiable foliage, however, are rare in the Morrison Formation as most sites preserve only carbonaceous fragments. Out of the thousands of fossil sites documented in the Morrison Formation in the Rocky Mountain region, only nine sites yield an abundance of leafy plant material. In 2016, the UGS Paleontology Section was funded by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to survey for fossils in the Morrison Formation of San Juan County near Blanding. While surveying an area of Morrison badlands, Jim Kirkland found some bone eroding from a hill. He then noticed that in addition to bone fragments, there was an abundance of macerated plant fragments and petrified driftwood. Based on extensive field experience, he knew these rocks might preserve a microsite, a site of very small animal and plant fossils. Microsites can typically only be identified by digging into fresh rock because the small fossils do not withstand surface weathering of the rock. Our UGS team later returned to the site along with fellow experts on Mesozoic-age microsites, Scott Madsen (retired UGS) and Jeff Eaton (retired Weber State University geologist). We noticed a band of dark-colored rock at the top of the hill overlying a volcanic ash. This dark layer was a finely laminated shale that contained well-preserved leaf fragments. We collaborated with John Foster (FHPR) and ReBecca Hunt-Foster (Dinosaur National Monument) to direct the investigations at this unique site. John is a leading expert on the paleontology of the Morrison Formation, and he enlisted the help of the late Sid Ash (Weber State University), an expert on Mesozoic plants, to help identify some of the many spectacular plant fossils that have been collected. Most sites are just known by their locality number, but when a site is special, we sometimes give it a name. This site has been dubbed the Jurassic Salad Bar. The fossils here belong to ferns, conifers, and relatives of modern ginkgos. A possible ginkgophyte, Czekanowskia turneri, occurs in dense mats, and the abundance of these fossils should lead to a much better understanding of this plant. Additionally, palynomorph samples first examined by the Smithsonian’s Carol Hotton yield a well-preserved assemblage of pollen and spores.

Simplified stratigraphy of the Jurassic Salad Bar site showing two prominent fossil levels: a lower level of pebbles with plant and bone fragments (Sa1134), and an upper finely laminated leaf level overlying a volcanic ash (Sa1212). This site has produced some of the best-preserved plant and invertebrate fossils ever found in the Morrison Formation.

The plants found at the Jurassic Salad Bar site are typical of wetland environments, potentially deposited in an oxbow lake or small pond. Work is ongoing with Carol Gee (University of Bonn, Germany) to better refine the stratigraphy and plant fossil assemblages. We expect that fossils from this site will greatly expand our knowledge of Jurassic-age plants. In addition to the exquisite plant fossils, this site has produced some other surprises. A giant water bug-like insect was described in 2020 with the help of an Argentinean colleague, Maria B. Lara (Centro de Ecología Aplicada del Litoral), and named Morrisonnepa jurassica. This insect is only the second documented in the Morrison Formation. Another interesting find is a rare crayfish that is one of the few ever found in the Morrison Formation. In addition, conchostracans (clam shrimps), insect eggs on leaves, fish, frogs, and salamanders have been found. We interpret one small splotch of tiny frog and salamander bones as a regurgitalite (fossil vomit) of a predatory amioid fish (based on scales found at the site). Although fossil plants may be more abundant at other sites, this locality has the best-preserved plant fossils ever found in the Morrison Formation. The fossils here are helping to expand our knowledge of Jurassic Period ecosystems and illustrate the importance of continuing fossil surveys even in formations that have been studied for well over a hundred years.

The opportunity for Carbon Capture Utilization and Sequestration (CCUS)—sometimes abbreviated to CCS—depends considerably on the type of rock present in the subsurface. (A) CO2 storage can occur by injecting gas deep underground into rock strata deemed unsuitable for other purposes. Modified from imagery provided by Global CCS Institute (https://www.globalccsinstitute.com/resources/ccs-image-library/). (B) A 4-inch-wide slabbed rock core from the Covenant oil field, Sevier County, Utah. The sandstone (buff-colored) is a good reservoir rock due to its porous and often permeable grains. The mudstone (red) is a good geological seal because it has low permeability and prohibits fluid and gas from escaping upwards. The sharp color contrast indicates the boundary between the seal and reservoir rock. The five holes in the rock core are where plugs were drilled into the rock and removed for analysis. (C) and (D) are photomicrographs of Jurassic-age Navajo Sandstone (reservoir rock) from the Covenant oil field that illustrate pore space availability (blue areas) for CO2 storage between quartz grains (white areas). Images B, C, and D modified from Chidsey and others (2020) (https://doi.org/10.34191/ss-167). Note the significant difference in scale from the well (kilometers) to the core (meters) to the rock grain and pore space (millimeters).

The opportunity for Carbon Capture Utilization and Sequestration (CCUS)—sometimes abbreviated to CCS—depends considerably on the type of rock present in the subsurface. (A) CO2 storage can occur by injecting gas deep underground into rock strata deemed unsuitable for other purposes. Modified from imagery provided by Global CCS Institute (https://www.globalccsinstitute.com/resources/ccs-image-library/). (B) A 4-inch-wide slabbed rock core from the Covenant oil field, Sevier County, Utah. The sandstone (buff-colored) is a good reservoir rock due to its porous and often permeable grains. The mudstone (red) is a good geological seal because it has low permeability and prohibits fluid and gas from escaping upwards. The sharp color contrast indicates the boundary between the seal and reservoir rock. The five holes in the rock core are where plugs were drilled into the rock and removed for analysis. (C) and (D) are photomicrographs of Jurassic-age Navajo Sandstone (reservoir rock) from the Covenant oil field that illustrate pore space availability (blue areas) for CO2 storage between quartz grains (white areas). Images B, C, and D modified from Chidsey and others (2020) (https://doi.org/10.34191/ss-167). Note the significant difference in scale from the well (kilometers) to the core (meters) to the rock grain and pore space (millimeters). Interbedded coal and sandstone in the Blackhawk Formation (just off SR-6, near Helper). Source : Mike Vanden Berg

Interbedded coal and sandstone in the Blackhawk Formation (just off SR-6, near Helper). Source : Mike Vanden Berg A few of the species from the Jurassic Salad Bar site. A) The reproductive organs of the fern Coniopteris hymenophylloides. B) Partial leaf of the ginkgophyte Sphenobaiera sp. C) Leaf bundles of the ginkgophyte Czekanowskia turneri. D) Partial leaf of the ginkgophyte Ginkgoites sp. E) Partial frond of the fern Coniopteris hymenophylloides. F) Abdominal segments and forewing of the giant water bug-like insect Morrisonnepa jurassica (Lara and others, 2020); abbreviation se = abdominal segment. G) Conchostracans, often called clam shrimp. All scale bars = 1 cm. Photos by Tom Howells, Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum.

A few of the species from the Jurassic Salad Bar site. A) The reproductive organs of the fern Coniopteris hymenophylloides. B) Partial leaf of the ginkgophyte Sphenobaiera sp. C) Leaf bundles of the ginkgophyte Czekanowskia turneri. D) Partial leaf of the ginkgophyte Ginkgoites sp. E) Partial frond of the fern Coniopteris hymenophylloides. F) Abdominal segments and forewing of the giant water bug-like insect Morrisonnepa jurassica (Lara and others, 2020); abbreviation se = abdominal segment. G) Conchostracans, often called clam shrimp. All scale bars = 1 cm. Photos by Tom Howells, Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum. The Drum Mountains meteorite at the Smithsonian. Flat surface at top is where the meteorite was cut for sectioning. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Drum_Mountains_meteorite_in_Museum_of_Natural_History.jpg

The Drum Mountains meteorite at the Smithsonian. Flat surface at top is where the meteorite was cut for sectioning. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Drum_Mountains_meteorite_in_Museum_of_Natural_History.jpg Large ice column in the entrance room of BBCC. February 2022.

Large ice column in the entrance room of BBCC. February 2022.