Geosights: White Rocks Tooele County, Utah

by Jim Davis

The northwest side of White Rock with an alcove near the summit. These large recesses in the rock lack any lichen growth and exhibit nested, cavernous weathering.

White Rocks is a collection of three light gray, dome-shaped hills of igneous rock in the southern Cedar Mountains in northwestern Utah. People come to White Rocks to hike, climb, camp, seek seclusion, take in the panoramic mountain and valley scenery, and to explore the numerous and diverse weathering features scored into their bald, steep-sided surfaces.

The names White Rocks and White Rock Complex are used to refer to the three largest isolated outcrops that rise starkly above the floor of a sandy, gently sloping 2-square-mile amphitheater. The amphitheater is bounded by various types of faults and encircled by the southern Cedar Mountains. The main outcrop, known officially as White Rock, is considerably larger than the other two outcrops combined, which are informally known as “south rock” and “west rock” and are nearly the same size. Several small, low-lying outcrops or knolls, all less than an acre in size and of the same igneous rock, are scattered across the amphitheater. A bubbling spring and pool, White Rock Spring, is at the west-edge of White Rock.

Stacked oblong-shaped caverns on a northwest-facing slope, east side of White Rock. Cavern at the bottom is 6 feet high at the entrance.

Collectively, White Rocks is composed of intrusive igneous rock, meaning the rock crystalized from molten magma as it slowly cooled beneath the surface of the Earth. The southern Cedar Mountains are situated in the Uinta-Tooele structural zone (see Survey Notes, v. 52, no. 2, p. 4–5), an ancient east-west-trending zone across northern Utah and eastern Nevada, where two blocks of continental crust likely converged around 1.7 billion years ago. Much later this zone of weakness was exploited by igneous activity that swept through Utah between 40 and 23 million years ago. This igneous episode is responsible for White Rocks, dated at nearly 39 million years ago, as well as other volcanic rocks in the southern Cedar Mountains.

A miniature arch, or window, with an opening about one foot high, at the base of the west side of White Rock.

The White Rocks outcrops are peppered with large- to small-sized alcoves and cavities, honeycomb-type, and other weathering features on recesses, vertical walls, and below overhangs. Excellent and larger-scale rock weathering forms occur all over the main White Rock and on the north-facing sides of the south rock. Light gray in color, the rock is patterned with blotches and expanses of primarily orange and lesser yellow, black, and tea-green lichen, preferential to north-facing slopes and absent from caverns. Streaks of iron and manganese stain the rock where storm water is channeled off the domes. Vegetation is sparse; junipers, grass, and cacti grow out of scattered pockets of soil and fractures in the rock. Sweeping views from the top of White Rock include Skull Valley to the north and the Stansbury Mountains to the east.

The rock of White Rocks is an attractive porphyritic dacite. Common to volcanic domes such as the Mt. St. Helens lava dome in Washington State, dacite is intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyolite. Porphyritic rock has large, visible crystals called phenocrysts in a finer-grained groundmass. The easily observable phenocrysts of White Rocks constitute about one-quarter of the rock. White plagioclase feldspar forms the largest crystals, accompanied by fractured, gemmy quartz, and flecked with blackish-brown biotite and amphibole. The grayish groundmass is an intergrowth of plagioclase, potassium feldspar, and quartz. A similar and much larger dacitic intrusion called Little Granite Mountain is located south of White Rocks on the Dugway Proving Ground military installation.

American geologist Clarence King visited White Rocks during the Fortieth Parallel Survey (1867–72) and wrote,

“The limestone body of Cedar Mountains . . . is accompanied by outbursts of volcanic rock.” King characterized the rock as a quartziferous trachyte, having “. . . a crystalline aggregation of sanidin[e] . . . reach an inch in length . . . brilliant black prisms of hornblende, flakes of biotite, and cracked, rounded grains of quartz.”

The expedition petrographer called the rock

“a very peculiar rhyolite,” observing that the quartz grains contain“. . . little glass inclusions, each with a dark bubble . . . the most extraordinary surcharging of them ever seen in this mineral.” The rock has another distinctive attribute—fine-grained, spheroidal to oblong inclusions that are linked to the development of some of the weathering cavities. King’s petrographer noted, “The crystalline groundmass contains locally some roundish, microfelsitic spots . . . which cannot be resolved into individual crystals.”

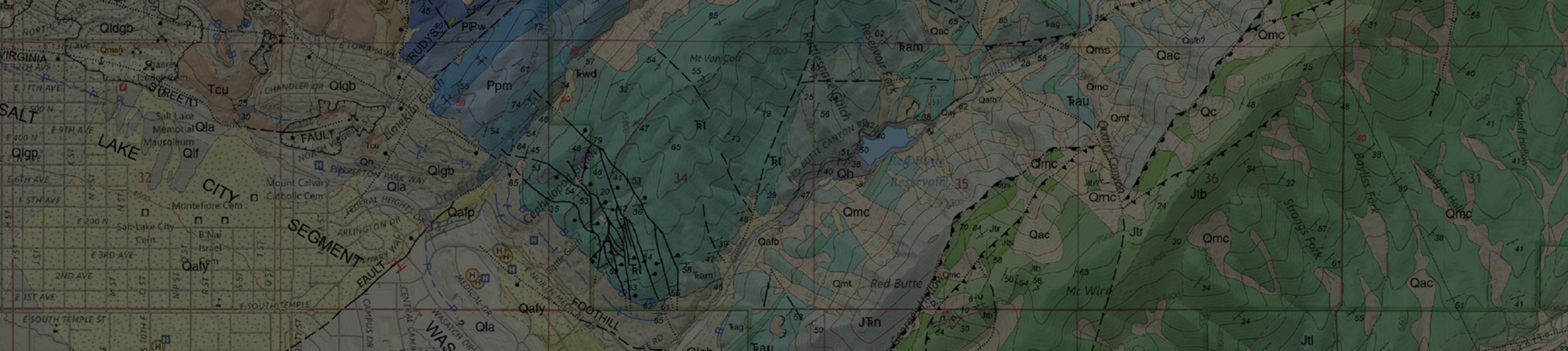

Virtual view of White Rocks using the Rush Valley 30’ x 60’ quadrangle geologic map from the UGS interactive Geologic Map Portal. Oblique view to the west with satellite base map. The pink hills are the three main outcrops at White Rocks and are surrounded by a plain of sand and silt—yellow and white with red dots. Limestone (blue) and lava flows (brown) encircle the White Rocks amphitheater. White Rock, at right, is about 44 acres and rises some 375 feet from the amphitheater floor. The nearby second white rock (south rock) rises 185 feet in height and is 12 acres in size, and in the distance, at left, the third white rock (west rock) rises 145 feet in height and covers 10 acres.

How to Get There:

From Salt Lake City go west on I-80 for 42 miles and take Exit 77 (Rowley, Dugway). Turn left and continue south on Highway 196 for 29.5 miles. A Bureau of Land Management (BLM) sign for “White Rocks” marks the turnoff. Turn right onto the gravel road (White Rock Road) and go west for 5.5 miles where the road splits. Take the left (southwest) fork onto a curvy road for 3.8 miles to reach the most visited part of the White Rocks area (west side of main White Rock). From here the road continues to loop around the main White Rock but shortly after passing White Rock Spring, a pond adjacent to the road about 60 feet in diameter (mostly dry in summer), the road degrades and is not recommended for low-clearance vehicles.

Notes:

There are no services in Skull Valley, including the nearby “closed city” of Dugway (on a military installation). Go with sufficient fuel and supplies. The Dugway Proving Ground is near the edge of the White Rocks amphitheater to the west and south; trespassing here is prohibited. White Rock has tall cliffs, steep slopes, and loose and crumbling rock surfaces; use caution when traversing the rock. The White Rocks area is frequented by climbers, scouts, horse riders and target shooters. Autumn and spring are the most pleasant times of year to visit and weekends can be more crowded. Approximately a dozen primitive, dispersed, first-come-first-served campsites are around the bases of the White Rocks, most at the main rock. There are no developed facilities, water, or restrooms. No fees are required. Dogs are allowed.

Land Ownership:

Nearly the entire amphitheater containing the White Rocks is Bureau of Land Management. Within a one-mile radius of White Rock is private, state, national forest, and military land.

Location:

Latitude 40.32244°N, Longitude 112.90191°W

Elevation:

Approximately 5,280 to 5,693