Groundwater Levels

Wells are holes drilled into the ground and are used to access water in an aquifer. They commonly have a pipe, known as casing, to hold the hole open. Old hand-dug wells used brick or stone as casing, but modern wells in Utah most commonly use steel or plastic pipe as casing. Most wells have either holes cut or sawed or a screen in the bottom of the casing to allow water to flow from the aquifer into the well. Most domestic wells use a small pump submersed in the well to bring water to the surface. Irrigation wells in Utah commonly use line-shaft pumps, where the motor on top of the well is connected to a rotating shaft that goes down into the well and connects to propellers that pump water.

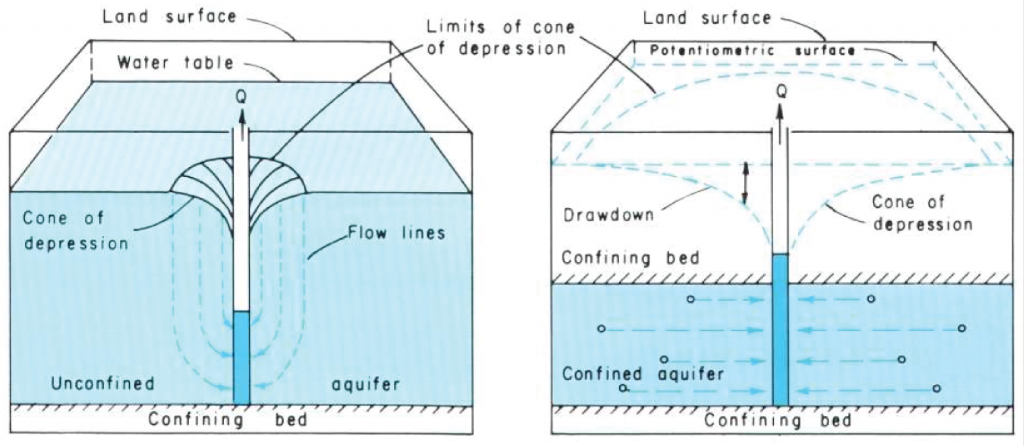

Decrease in groundwater level called a cone of depression in an unconfined aquifer (left) and a confined aquifer (right) (from USGS Water Supply Paper 2220).

Water level in wells can vary over time. Natural variation can be caused by changes in the amount of water stored in the aquifer. Smaller natural water level changes can be caused by barometric pressure or even gravitational forces. Humans can also influence groundwater level. As a well pumps water from an aquifer, it creates a cone-shaped depression in the groundwater level around the well, aptly named a cone of depression. When a cone of depression intersects other cones of depression, the drawdown observed in the well is increased. When a cone of depression intersects a stream, flow in the stream will be reduced. Cones of depression can be estimated based on an equation known as the Theis equation. You can experiment with this equation on the Utah Division of Water Rights website.

Groundwater Level Decline

If groundwater discharge and recharge to an aquifer are imbalanced where discharge exceeds recharge, then groundwater storage is depleted, and groundwater levels decline. When groundwater storage is depleted, natural sources of discharge, like springs and groundwater-dependent wetlands, can be replaced by human activity-related sources like well pumping.

In those cases, water flow to natural areas of discharge decreases or ceases and the springs, streams, or wetlands may dry up completely. Groundwater mining or groundwater overdraft occurs when the rate of groundwater extraction exceeds the rate of groundwater recharge. Groundwater mining can cause dry wells, reduced spring and stream flows, and land subsidence.

Subsidence and Ground Cracking

In unconsolidated and semiconsolidated aquifers, water pressure can actually act as a structural support agent. Groundwater in aquifer pore spaces and fractures supports the weight of the overlying sediment or rock, holding the pore spaces open. When water is removed from an aquifer, pore spaces and fractures collapse, causing compaction of the aquifer. The water pressure no longer supports the aquifer structure, causing compaction of the aquifer skeleton. Porosity and permeability are permanently decreased from this compaction. Compaction of the aquifer materials causes the land surface to sink, known as subsidence. Some sediment types, like clay, are especially susceptible to changes in saturation, and can halve in volume as a result of this dewatering.

Differences in type and thicknesses of unconsolidated sediments can lead to different amounts of subsidence. Differential compaction is commonly expressed on the land surface as earth fissures and scarps, and can cause reversal of drainage gradients. Subsidence from declining groundwater levels has been documented in Parowan and Cedar Valleys, Iron County, Utah. Groundwater levels have declined more than 100 feet in certain parts of Cedar Valley, causing earth fissures and measurable amounts of land subsidence.

Groundwater Level Monitoring

To observe changes in groundwater storage over time, the Utah Geological Survey has created and maintains several groundwater monitoring networks throughout Utah. The U.S. Geological Survey also maintains a widespread network of wells in which they measure groundwater levels annually or, in some cases, more frequently.

Snake Valley straddles the border between Nevada and Utah, where some of the groundwater recharging in Nevada naturally flows to the Utah side of the valley, ultimately ending up in discharge zones like wetlands and Fish Springs. The UGS has monitored groundwater levels in Snake Valley for more than 12 years. More than 70 monitoring wells and six gauges that measure spring flow compose the Snake Valley Monitoring Network.