Glad You Asked: What do landslides, glaciers, and faults have to do with the lakes on the Wasatch Plateau?

by Lance Weaver

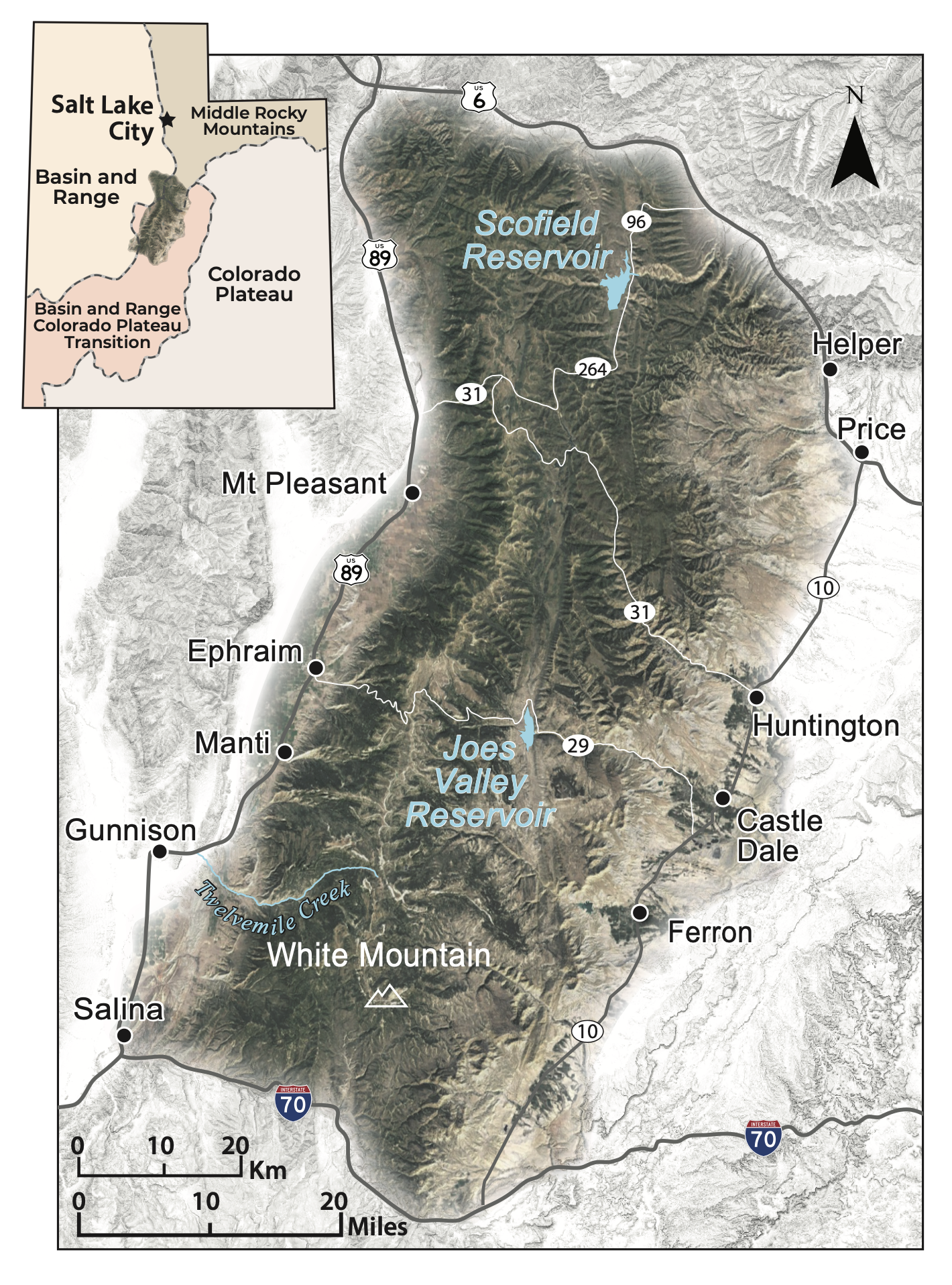

The Wasatch Plateau is located south and east of the southernmost part of the Wasatch Range in central Utah and is in the transition zone between the Colorado Plateau and the Basin and Range physiographic provinces. The plateau is a table-like mountain range with an abundance of lakes and reservoirs along its axis. These many lakes and reservoirs are the result of three very different geological processes that continue to shape the area. These include landslides, which are responsible for most of the plateau’s smaller lakes; extensional faulting, which created valleys (or grabens) that accommodate the plateau’s largest modern reservoirs as well as a few mid-size lakes; and Pleistocene-age (about 2.6 million to 12,000 years ago) glaciation, which created many of the plateau’s smaller high-elevation lakes.

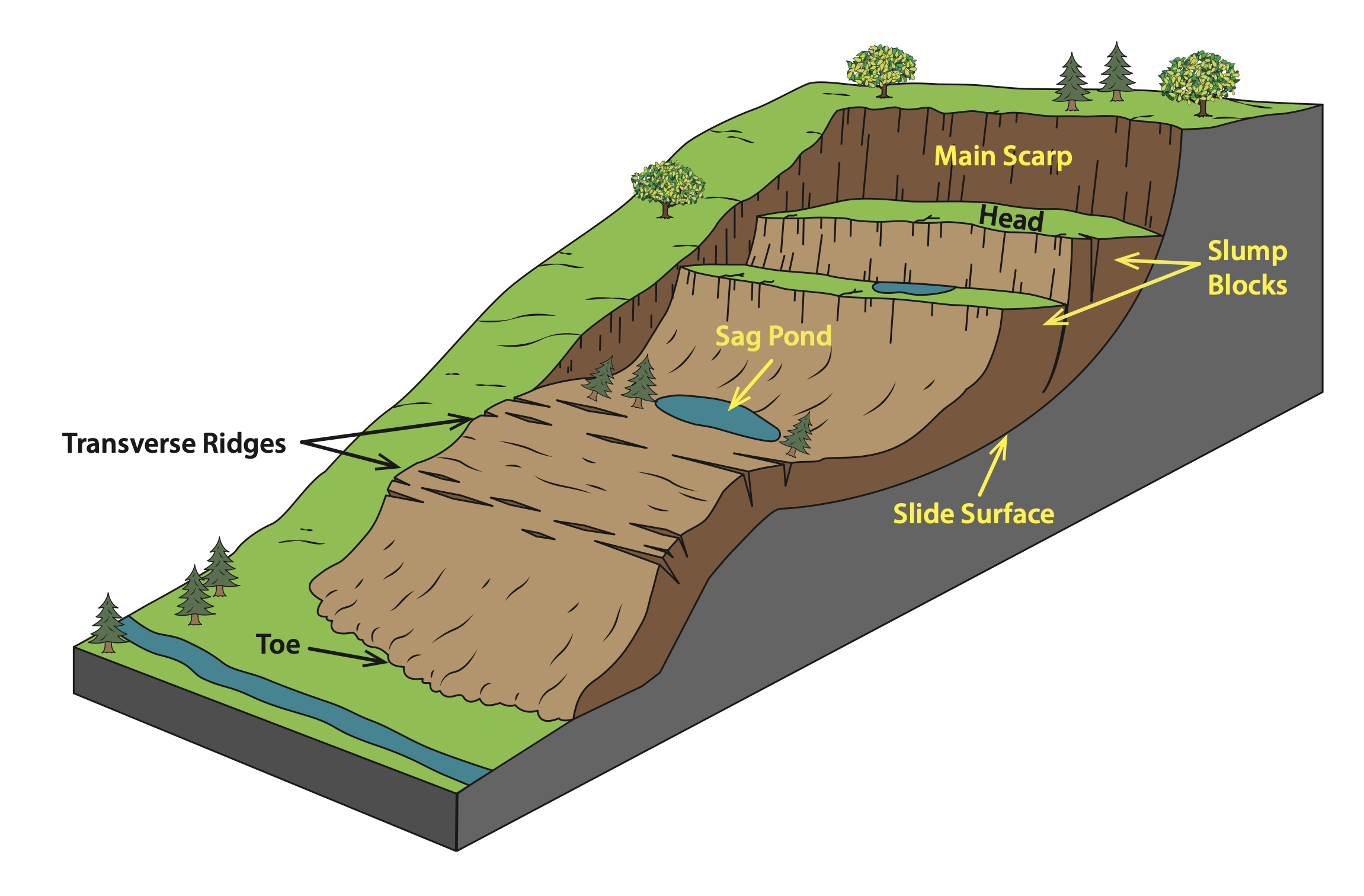

The Wasatch Plateau is home to many mid- to high-elevation wooded shallow ponds and lakes that create amazing opportunities for camping, fishing, and recreating. However, most do not realize that the small, relatively flat basins that house many of these lakes are actually closed depressions that form near the uppermost part, or head of large ancient landslides. Although the bottom, or toe, of landslides can often form lakes as they dam stream drainages, few of these types of lakes last because they are prone to overtopping and erosion. However, the top part of landslides commonly form what is known as a sag pond or closed depression just below the head. The Wasatch Plateau contains many of these with classic examples existing in areas such as Mayfield Canyon’s Twin Lake or the many ponds in the Spring Hill area and other headwaters of Twelvemile Creek. Ponds can also form between the toe and head of the landslide due to the uneven, jumbled, or hummocky topography, such as Slide Lake west of Joes Valley Reservoir.

Landslide morphology showing the pond-forming, closed depressions that develop below the head of a landslide.

The abundance of ancient landslides that created these lakes and ponds is largely the result of the composition of the North Horn Formation. This formation formed during the Late Cretaceous Period and Early Paleocene Epoch, approximately 75 to 60 million years ago, and consists of a series of alternating layers of sandstone and clay-rich siltstone and mudstone. These clay-rich layers make the formation particularly susceptible to landslides. When wetted, the clay layers become weak surfaces that allow the rock layers on top to move down slope.

Occasionally, the instability of the North Horn and a few other similar geologic units has led to massive modern landslides and debris flows that have caused significant damage to infrastructure on the plateau.

One such example occurred in Twelvemile Canyon, which has a long history of damaging landslides. In the spring of 1983, a massive landslide in the canyon temporarily blocked the creek, which soon overtopped the natural dam and created a debris flow. The debris flow traveled 2.4 miles down the South Fork of Twelvemile Creek before burying part of Pinchot Campground. Another 1983 landslide, below nearby Twin Lake, closed the road and threatened to block Twelvemile Creek entirely. Less than two decades later, in 1998, another large landslide from the North Fork of Cooley Creek traveled 1.8 miles down the South Fork of Twelvemile Creek, depositing large amounts of landslide material in the creek. In addition to these historical landslides, prehistoric landslides are common in the canyon, and evidence shows that some have blocked and deflected creeks.

Block diagram showing the formation of a graben between normal faults as Earth’s crust extends and pulls apart.

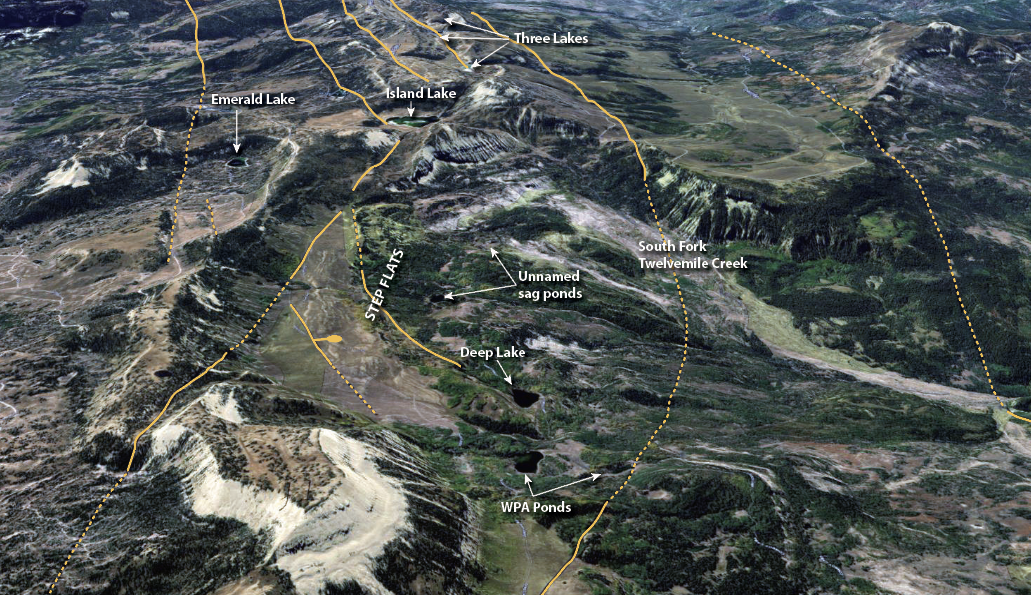

The second process responsible for the location of the largest lakes on the Wasatch Plateau is extensional faulting. The Wasatch Plateau has many north-to-south-oriented normal faults that are created by the incredibly slow westward extension or pulling apart of the plateau. The rocks on either side of a normal fault move up or down relative to each other and the down-dropped side creates a depression or valley called a graben. Several major Wasatch Plateau lakes, such as Scofield Reservoir and Joes Valley Reservoir, are located in such fault-bounded valleys. A string of smaller graben lakes also exists along the upper axis of the Wasatch Plateau in the Island Lake and Three Lakes area of White Mountain.

The third factor responsible for the many lakes on the Wasatch Plateau is glaciation. During the Pleistocene the upper elevations of the plateau accumulated several sprawling glaciers. Existing mostly above an elevation of 9,500 feet, these glaciers carved out many notable steep-sided, bowl-shaped depressions called cirques, leaving behind several small lakes and ponds called tarns. Some examples of lake basins formed by glaciation are Ferron Reservoir, Blue Lake, and Emerald Lake, which are located in the high southeast section of the Wasatch Plateau.

The lakes, ponds, and reservoirs of Utah’s Wasatch Plateau are hidden gems for recreation. A trio of geological processes contributed to the formation of its many small and large water bodies, which include a unique combination of ponds from landslides, reservoirs in extensional faulted valleys, and lakes in ancient glacial cirques.

Many of the Wasatch Plateau’s lakes are visible in this aerial image looking southward along the axis of Skyline Drive east of Gunnison, Utah. Deep Lake, the WPA ponds, and many of the other unnamed lakes and ponds of the Step Flats area are sag ponds created at the head of landslides within the Twelvemile Creek drainage. Island Lake and several other small lakes along the axis of the Plateau are graben lakes bounded by normal faults. Solid and dashed orange lines are normal faults, the bar and ball symbol indicates the down-dropped side of the fault. Emerald Lake is in a Pleistocene-age glacial cirque. Aerial imagery courtesy of ESRI, Earthstar Geographics.

Riparian wetlands of Moab's Mill Creek, where invasive species removal and cattle fencing has allowed native willows to grow again.

Riparian wetlands of Moab's Mill Creek, where invasive species removal and cattle fencing has allowed native willows to grow again.