Landforms

The earth’s surface is constantly remodeled by various geological processes. The changes are one of the most exciting things about geology—not only are they continuous, but in many cases, observable. Some geological processes, such as those that make mountains or wear them down, typically take place at imperceptible rates. Sudden events, however, can change the landscape in a minute (for example, a single earthquake can create a 10-foot-high [3 meter] fault scarp, alter stream courses, and drop the valley floor 3 feet [1 meter]).

Utah is the ideal place to observe geology in action. The state contains many types of landforms, such as mountains, plateaus, mesas, river-eroded canyons, glacier-eroded canyons, volcanoes, and basins.

Crustal plate movement, mountain building (except some volcanic mountain building), and erosion are part of the slow evolution of Earth’s landscape. This evolution is sporadically interrupted by more sudden geological events, such as earthquakes (following the Borah Peak, Idaho earthquake in 1983, the mountain range rose 8 inches [20 centimeters], and the adjacent valley dropped about 4 feet [1.2 meters]) and volcanic activity (in Mexico in 1943, a volcano called Paricutin appeared in a farmer’s field and rose 525 feet [160 meters] within a week). Erosion can also happen quite suddenly, and in some cases, may be greatly accelerated by human activities. Flash floods can erode more than 10 inches (25 centimeters) of soil in only a few hours.

By observing landforms, we can learn where geological processes, including erosion, mountain building, crustal extension, earthquakes, geothermal activity, landslides, and rockfalls are currently active in Utah.

Mountains

Click image to view gallery.

Definitions

Volcanic Mountain – A mountain that forms as rising magma erupts onto Earth’s surface.

Fault-Block Mountain – A mountain that rises along a fault.

Folded Mountain – A mountain formed by compression of the earth’s crust.

Dome Mountain – A mountain produced where a region of flat-lying sedimentary rocks is bowed upward to form a structural dome.

Read More:

What are those lines on the mountain? From bread lines to erosion-control lines

Glaciers

Click image to view gallery.

Definitions

Glacier – A large sheet of moving ice.

Cirque – Semi-circular bowl formed at the head of a glacier.

Moraine – Ridge-like landform deposited at the end or sides of a glacier.

Read More:

Volcanoes

Click image to view gallery.

Definitions

Volcanoes can create mountains, craters, and islands.

Cinder Cone – A small cone-shaped volcano with steep sides.

Shield Volcano – A wide, low-profile volcano shaped like a flattened dome.

Composite (Stratovolcano) Volcano – A very tall and large volcano with steep sides.

Crater – A circular depression at the top of a volcano formed by collapse from a large eruption.

Caldera – A large volcanic crater, especially one formed by a major eruption leading to the collapse of the mouth of the volcano.

Island – A land mass (smaller than a continent) that is surrounded by water. One of the most prominent ways islands form is from volcanic arcs and hot spots.

Read More:

Earthquake-Related Landforms

Click image to view gallery.

Definitions

Fault – A crack in the earth’s surface along which two rock masses slide past one another.

Fault Scarp – A steep break (escarpment) that forms where vertical fault movement reaches the ground surface.

Read More:

Plateaus

Click image to view gallery.

Definitions

Plateau – A large, wide landform that is much higher than the adjacent land.

Mesa – An isolated, wide, flat-topped landform higher than the surrounding land with steep cliff sides. Smaller than a plateau, mesas are wider than they are high.

Butte – An isolated flat-topped landform higher than the surrounding land with steep cliff sides. Buttes are as high as they are wide.

Pinnacle – A rock spire that is taller than it is wide.

Read More:

Arches

Click image to view gallery.

Definitions

Arch – The semicircular shape of an arch is actually the most effective load-bearing form in nature because of the manner in which it distributes the compressional stresses and eliminates the extensional stresses in the surrounding rock.

Bridge – The only difference between an arch and a bridge is that a bridge forms initially by stream erosion.

Read More:

Why are there so many natural arches in Utah?

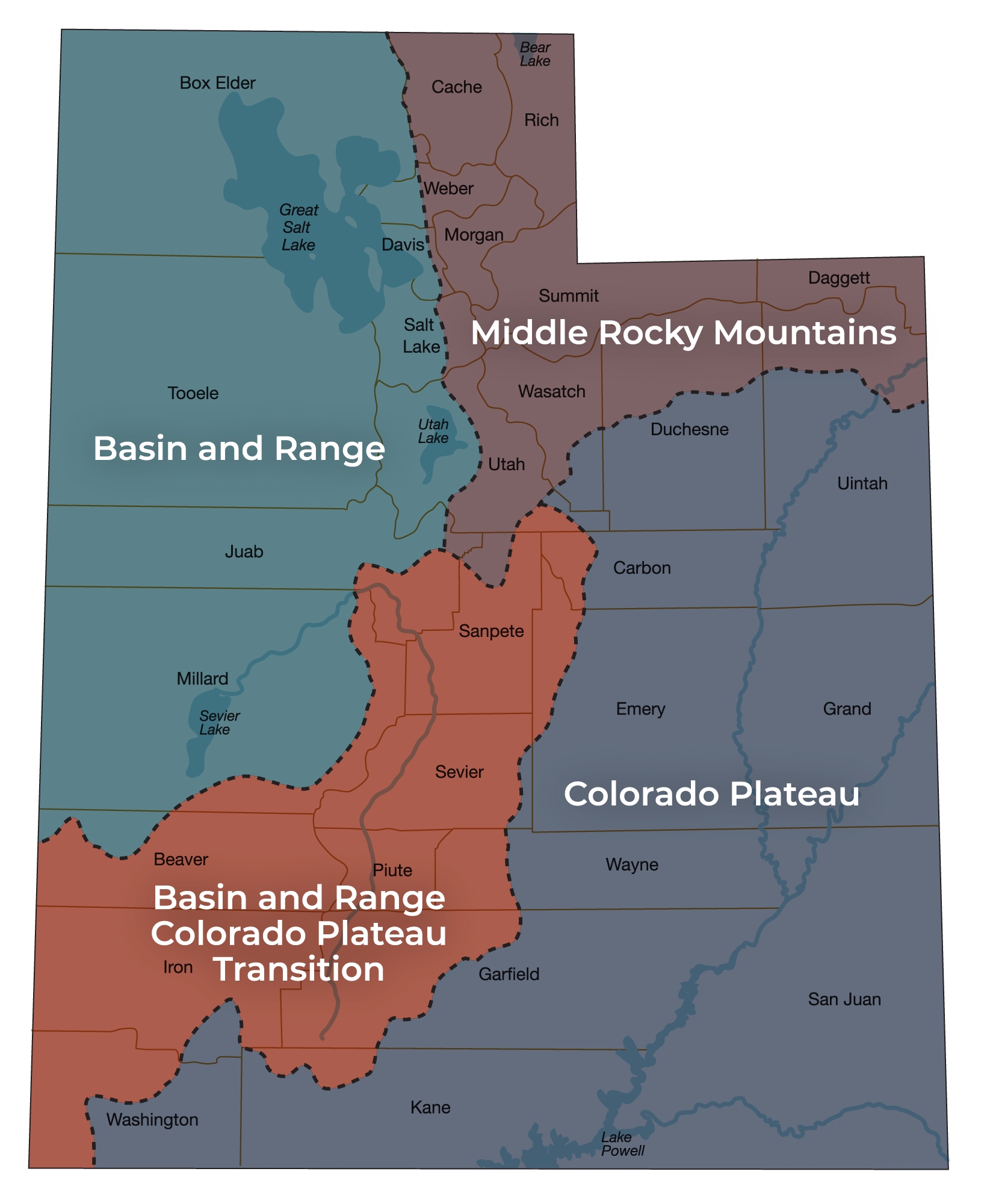

Physiographic Provinces

Basin and Range Province

Steep, narrow, north-trending mountain ranges separated by wide, flat, sediment-filled valleys characterize the topography of the Basin and Range Province. The ranges started taking shape around 17 million years ago when the previously deformed Precambrian (over 540 million years old) and Paleozoic (~540 to ~250 million years old) rocks were slowly uplifted and broken into huge fault blocks by extensional stresses that continue to stretch the earth’s crust.

Colorado Plateau Province

In contrast with the Basin and Range Province, a thick sequence of largely undeformed, nearly flat-lying sedimentary rocks characterize the Colorado Plateau province. Erosion sculpts the flat-lying layers into picturesque buttes, mesas, and deep, narrow canyons.

For hundreds of millions of years sediments have intermittently accumulated in and around seas, rivers, swamps, and deserts that once covered parts of what is now the Colorado Plateau. Starting about 10 million years ago the entire Colorado Plateau slowly but persistently began to rise, in places reaching elevations of more than 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) above sea level. Miraculously it did so with very little deformation of its rock layers. With uplift, the erosive power of water took over to sculpt the buttes, mesas, and deep canyons that expose and dissect this “layer cake” of sedimentary rock.

Middle Rocky Mountains Province

High mountains carved by streams and glaciers characterize the topography of the Middle Rocky Mountains province. The Utah part of this province includes two major mountain ranges, the north-south-trending Wasatch and east-west-trending Uintas. Both ranges have cores of very old Precambrian rocks, some over 2.6 billion years old, that have been altered by multiple cycles of mountain building and burial.

Basin and Range – Colorado Plateau Transition Zone

The Basin and Range–Colorado Plateau transition zone is a broad region in central Utah containing structural and stratigraphic characteristics of both the Basin and Range Province to the west and the Colorado Plateau province to the east.

The boundaries are the subject of some disagreement, resulting in various interpretations using different criteria. Essentially, extensional tectonics of the Basin and Range has been superimposed upon the adjacent coeval uplifted blocks of the Colorado Plateau and Middle Rocky Mountains. The result is that block faulting, the principal feature of the Basin and Range, extends tens of kilometers into the adjacent provinces forming a 100-km-wide (60 mi) zone of transitional tectonics, structure, and physiography.

Read More: