Glad You Asked: What’s With All This Dust?

by Abby Mangum

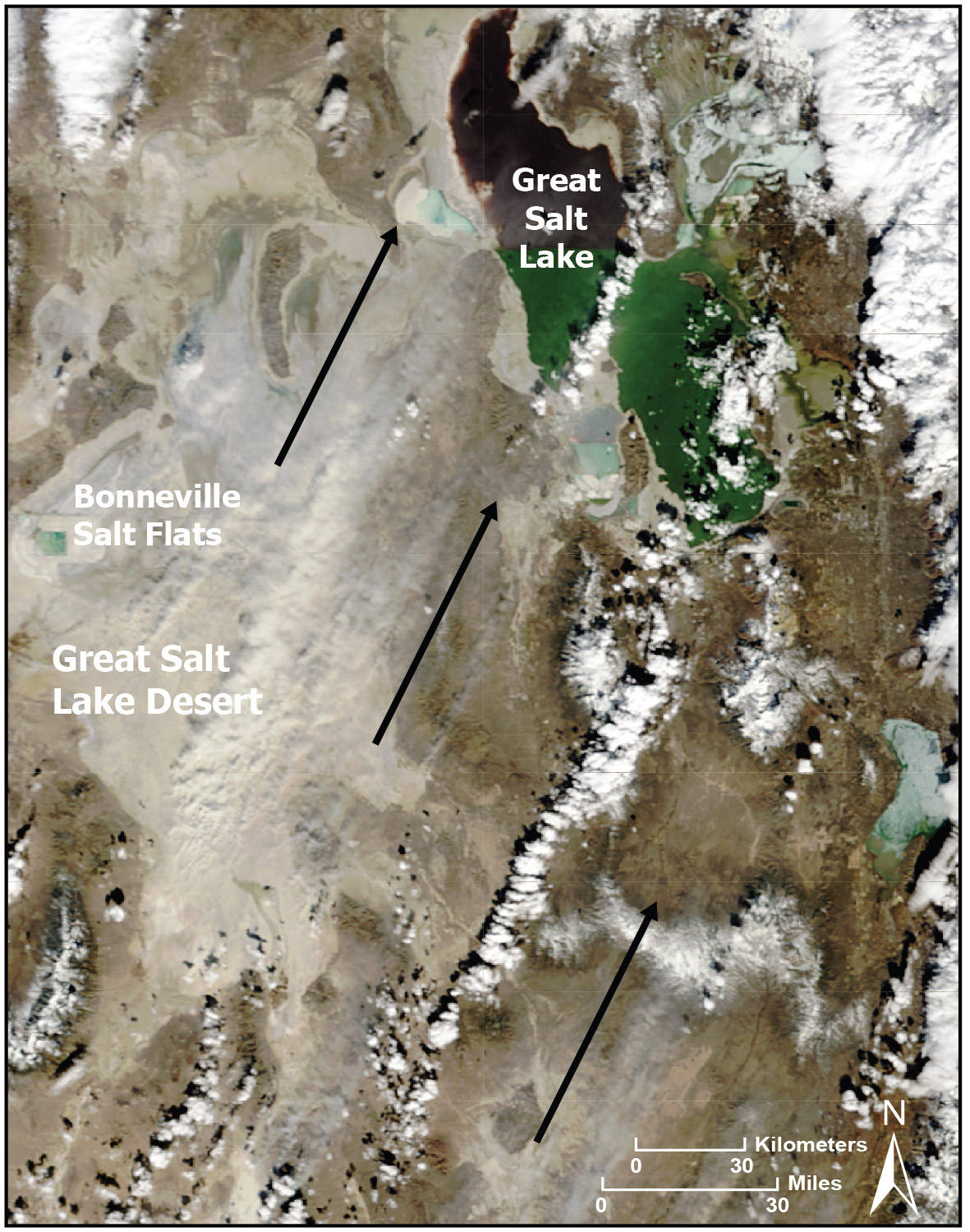

A satellite image of a dust storm sweeping across the Great Salt Lake Desert towards the Wasatch Front. Taken March 4, 2009, by MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) on NASA’S Terra satellite. The dust shows up as pale, rippling clouds above the duller tan desert below. The arrows indicate the northeast direction the dust storm is traveling.

After a long winter of inversions and cabin fever, it is normal to crave fresh air. But then suddenly, spring comes, and the air is full of haze again! What is going on? The answer: dust.

What are dust storms?

Utah historically experiences frequent dust storms from March to May, with a secondary peak in the fall. Most of these dust events are a result of cold fronts and occasional thunderstorms in the summer. Basin and Range topography (north-south-oriented valleys and mountains) funnels strong, southwesterly winds produced from these storms, transporting dust north towards the Wasatch Front.

Dust problems

This dust consists of clay and silt-sized sediment (2–50 micrometers in diameter), which are small enough to be easily transported by wind. However, the small size of these particles also means they are easily inhaled, potentially causing health issues such as pneumonia and Valley fever, an illness caused by inhaling airborne spores of a fungus called Coccidioides that lives in the soil of arid regions. Dust also reduces visibility, which can lead to roadway accidents, and can contain various organisms, minerals, and metals that affect air quality and water resources. An additional environmental impact of the dust is that it can cause early onset melting of the mountain snowpack. A dark layer of dust on the snowpack reduces the snow’s albedo (reflectivity), causing the snow to absorb more sunlight and melt faster. This early snowmelt can disrupt Utah’s water management practices, and the dust can introduce foreign minerals and organisms into the alpine environment.

Where does dust come from?

Dust sampling locations in Utah. Playa dust samplers are placed in dry lakebeds. Urban dust collectors are placed on rooftops of buildings. Snow dust samples are collected in the mountain snowpack. These samplers and associated data are courtesy of Greg Carling, researcher and professor at Brigham Young University.

Much of the dust reaching the Wasatch Front comes from dry lakebeds (playas) in western and southwestern Utah. Arid regions such as Sevier Dry Lake, the Bonneville Salt Flats, and other playas in this area are particularly vulnerable to drought-related changes in vegetation, as well as impacts from grazing, mining, urban development, and off-road vehicle travel. A fraction of dust that researchers collected along the Wasatch Front contains man-made aerosols from urban and industrial sources, such as mining and smelting.

Researchers across Utah are working hard to understand dust sources and track their impacts. One way they are doing this is through “fingerprinting”: identifying a dust sample’s unique traits, like its chemical makeup, microbes, or tiny differences in atoms (called isotopes). Like matching a fingerprint to a suspect, these clues help trace the dust back to its source. For example, scientists might find that the dust on your car in Salt Lake City matches the chemical “fingerprint” of sediment from a dry lakebed hundreds of miles away. Researchers collect dust samples throughout the state, focusing on the west desert, urban areas (via rooftop samplers), and snow in the Uinta Mountains. They then prep these samples in a lab by exposing them to a series of acidic leaching solutions, and then analyze them using an instrument that measures the isotope ratios of elements, like the amount of Strontium-87 to Strontium-86. These ratios are unique to specific regions, and researchers can compare them between sample sites to determine the “source” (dust origin) and “sink” (where dust gets deposited). It is vital to continue monitoring these sources so that future management decisions can be made.

What can we do?

Less dust in the air means cleaner lungs, safer roads, and a healthier winter snowpack. You can start making a difference today! Mindful choices, like conserving water, using best practices for agriculture and grazing management, and even staying on designated roads while exploring, can help reduce dust emissions. As we all work together, our efforts can have a significant impact. More research is needed to mitigate this problem, but mindful land and water use can help reduce dust storms in the future.