Ice Age

The time that we typically think of as the “Ice Age” peaked about 18,000 years ago. We are presently living in an interglacial, or warm period, between glacial episodes in the current ice age that began about 2.6 million years ago, spanning the entire Quaternary Period. Ice ages have occurred several times during Earth’s history. Major ice ages occurred during the Precambrian (~800-600 million years ago), the Ordovician to Silurian (~470-430 million years ago), the Carboniferous to Permian (~350-250 million years ago), and in the Pleistocene and Holocene Epochs (~2.6 million years ago to present).

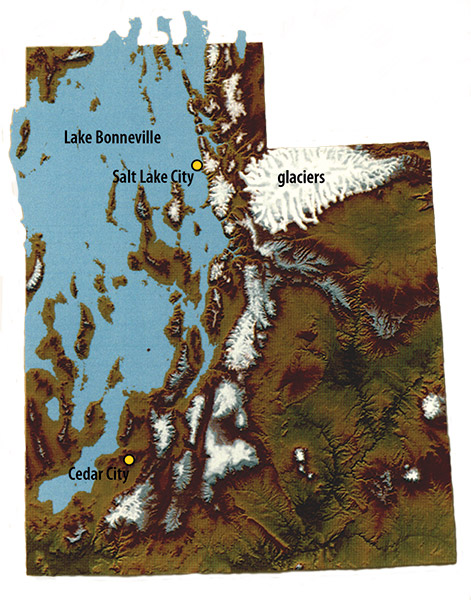

Glaciers covered most of the high mountains of Utah periodically during the Ice Age. Lake Bonneville, a large freshwater lake, covered most of western Utah from 30,000 to 13,000 years ago. Great Salt Lake is the remnant of this Ice Age lake. The animals that lived in Utah during the Ice Age included many of the same animals that we find here today, as well as many extinct forms such as mammoths, mastodons, ground sloths, and saber-toothed cats.

Geologic Setting

Around 18,000 years ago, during the last glacial cycle peak in Utah, Lake Bonneville covered a large expanse of western Utah and parts of Idaho and Nevada. There were also alpine glaciers present in the Uinta Mountains and Wasatch Range. The erosive power of these large glaciers, hundreds of feet thick, sculpted the mountainous landscape of the Wasatch, creating much of the beautiful mountain scenery we have today. The cooler, wetter climate in the late Pleistocene contributed to Lake Bonneville’s rise to its maximum level as well as the growth of glacial ice in mountainous regions.

Read More:

Ice Age Wildlife

The animals that lived in Utah during the Ice Age included many of the same animals that we find here today, as well as many extinct forms such as mammoths, mastodons, ground sloths, and saber-toothed cats. Many of the extinct Pleistocene animals were very large and have living relatives who are usually much smaller. These large animals are referred to as the “Pleistocene Megafauna.” They became extinct at the end of the Ice Age, about 10,000 years ago.

Gravel quarries along the Wasatch Front contain the bones of many Ice Age animals. These gravels are deltaic deposits formed in Lake Bonneville. The animals that roamed the shores of Lake Bonneville included big-horn sheep (Ovis), horses (Equus), and bison (Bison), whose living relatives are found in Utah today, as well as animals such as musk oxen (Bootherium bombifrons), camels (Camelops hesternus), and giant ground sloths (Megalonyx jeffersoni), who have living relatives in other parts of the world.

Musk oxen are found today only in the Arctic. Ground sloths are now extinct, but are related to the much smaller tree sloths that live in South America. Horses and camels are both native to North America. After their expansion into other parts of the world, camels and horses became extinct in North America at the end of the Ice Age. Horses living in Utah today are descendants of the horses brought to the New World by the Spanish.

Saber-toothed Cat

The saber-toothed cat (Smilodon) from the late Pleistocene was the size of a lion and had enlarged canines that looked like small elephant tusks. Unlike lions, which have long tails that help provide balance when the animals run, Smilodons had bobtails which suggest that they probably did not chase down prey, but charged from ambush instead, waiting for prey to come close before attacking. The saber-toothed cat went extinct about 10,000 years ago.

Smilodon californicus fossils are known from a site called Silver Creek, which is near Park City. The Silver Creek site is approximately 40,000 years old and contains fossils from animals that are still living today as well as from many that are extinct. The only saber-toothed cat bones found at Silver Creek are a canine tooth, a neck bone, and a humerus (front leg bone). The cast skeleton at the Children’s Museum of Utah comes from the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, California. Hundreds of skeletons of predators such as the saber-toothed cat and the dire wolf (Canis dirus) have been found in the tar deposits at Rancho La Brea. Sites like this are called predator traps.

What is Left of the Last Ice Age Today?

Geologic Features

During the last Ice Age, glaciers advanced down Little Cottonwood Canyon in the Wasatch Range to the canyon mouth. The glaciers scoured the canyon floor and walls, leaving behind a classic “U-shaped” valley that is characteristic of glacial erosion. A trimline marks the maximum upper level of the margins of a glacier. The Wasatch and Uinta mountains also contain glacier-carved horns, cirques, arêtes, moraines, and more that showcase the Ice Age glacial activity that helped form northern Utah’s dramatic mountain landscape.

On a smaller scale, glacial erratics are rock fragments that have been carried by glacial ice and deposited some distance from their original source. Erratics can be as small as a pebble to as large as a house! Many erratics are located near the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon. Glacial striations are scratches and gouges cut into bedrock from the movement of glaciers. In the Wasatch and Uinta Ranges, striations are an excellent indicator of where a glacier existed and traversed.

Read More:

Lake Bonneville Shorelines

Lake Bonneville was the largest late Pleistocene lake in western North America. The lake rose (transgressed) and fell (regressed) throughout its existence due to climatic changes in the Bonneville basin. Rocks, sediment deposits, shells and fossils, and numerous erosional and depositional shoreline landforms characterize what is left of the lake. At its highest level (Bonneville level), the lake covered about 20,000 square miles of western Utah and parts of adjacent Nevada and Idaho and was about 1,000 feet deep at and around the area of present-day Great Salt Lake. The Bonneville shoreline is spectacularly etched into the northern flank of the Traverse Mountains, particularly at Steep Mountain, but you can also see ancient shorelines in the slopes of the Wasatch Range, Antelope Island, and many other mountains that bordered the lake or that were islands and peninsulas during the ice-age lake’s lifetime. Aqueous remnants of Lake Bonneville include Great Salt Lake, Utah Lake, and Sevier Lake.

Read More:

Mammals

Fossil records provide evidence that mammals that now seem confined to isolated mountain ranges in the Great Basin were widespread in low elevation settings toward the end of the Pleistocene. In addition to documenting range limits, the fossil record also shows the prehistoric abundances of these species. This is particularly true of the American pika whose fossils are found in enormous numbers. Today, the American pika is found in some of the high mountain ranges of Utah, where it prefers rocky slopes above the treeline. The wolverine lived during the Ice Age in small numbers (and still may be found) in the high mountainous areas of the state. Wolverines prefer alpine tundra and mountain forest habitats that are not frequented by humans.

Read More:

Geologic Features

During the last Ice Age, glaciers advanced down Little Cottonwood Canyon in the Wasatch Range to the canyon mouth. The glaciers scoured the canyon floor and walls, leaving behind a classic “U-shaped” valley that is characteristic of glacial erosion. A trimline marks the maximum upper level of the margins of a glacier. The Wasatch and Uinta mountains also contain glacier-carved horns, cirques, arêtes, moraines, and more that showcase the Ice Age glacial activity that helped form northern Utah’s dramatic mountain landscape.

On a smaller scale, glacial erratics are rock fragments that have been carried by glacial ice and deposited some distance from their original source. Erratics can be as small as a pebble to as large as a house! Many erratics are located near the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon. Glacial striations are scratches and gouges cut into bedrock from the movement of glaciers. In the Wasatch and Uinta Ranges, striations are an excellent indicator of where a glacier existed and traversed.

Read More:

Lake Bonneville Shorelines

Lake Bonneville was the largest late Pleistocene lake in western North America. The lake rose (transgressed) and fell (regressed) throughout its existence due to climatic changes in the Bonneville basin. Rocks, sediment deposits, shells and fossils, and numerous erosional and depositional shoreline landforms characterize what is left of the lake. At its highest level (Bonneville level), the lake covered about 20,000 square miles of western Utah and parts of adjacent Nevada and Idaho and was about 1,000 feet deep at and around the area of present-day Great Salt Lake. The Bonneville shoreline is spectacularly etched into the northern flank of the Traverse Mountains, particularly at Steep Mountain, but you can also see ancient shorelines in the slopes of the Wasatch Range, Antelope Island, and many other mountains that bordered the lake or that were islands and peninsulas during the ice-age lake’s lifetime. Aqueous remnants of Lake Bonneville include Great Salt Lake, Utah Lake, and Sevier Lake.

Read More:

Mammals

Fossil records provide evidence that mammals that now seem confined to isolated mountain ranges in the Great Basin were widespread in low elevation settings toward the end of the Pleistocene. In addition to documenting range limits, the fossil record also shows the prehistoric abundances of these species. This is particularly true of the American pika whose fossils are found in enormous numbers. Today, the American pika is found in some of the high mountain ranges of Utah, where it prefers rocky slopes above the treeline. The wolverine lived during the Ice Age in small numbers (and still may be found) in the high mountainous areas of the state. Wolverines prefer alpine tundra and mountain forest habitats that are not frequented by humans.

Read More: