Historical Maps – More Than Meets The Eye

By Stephanie Earls

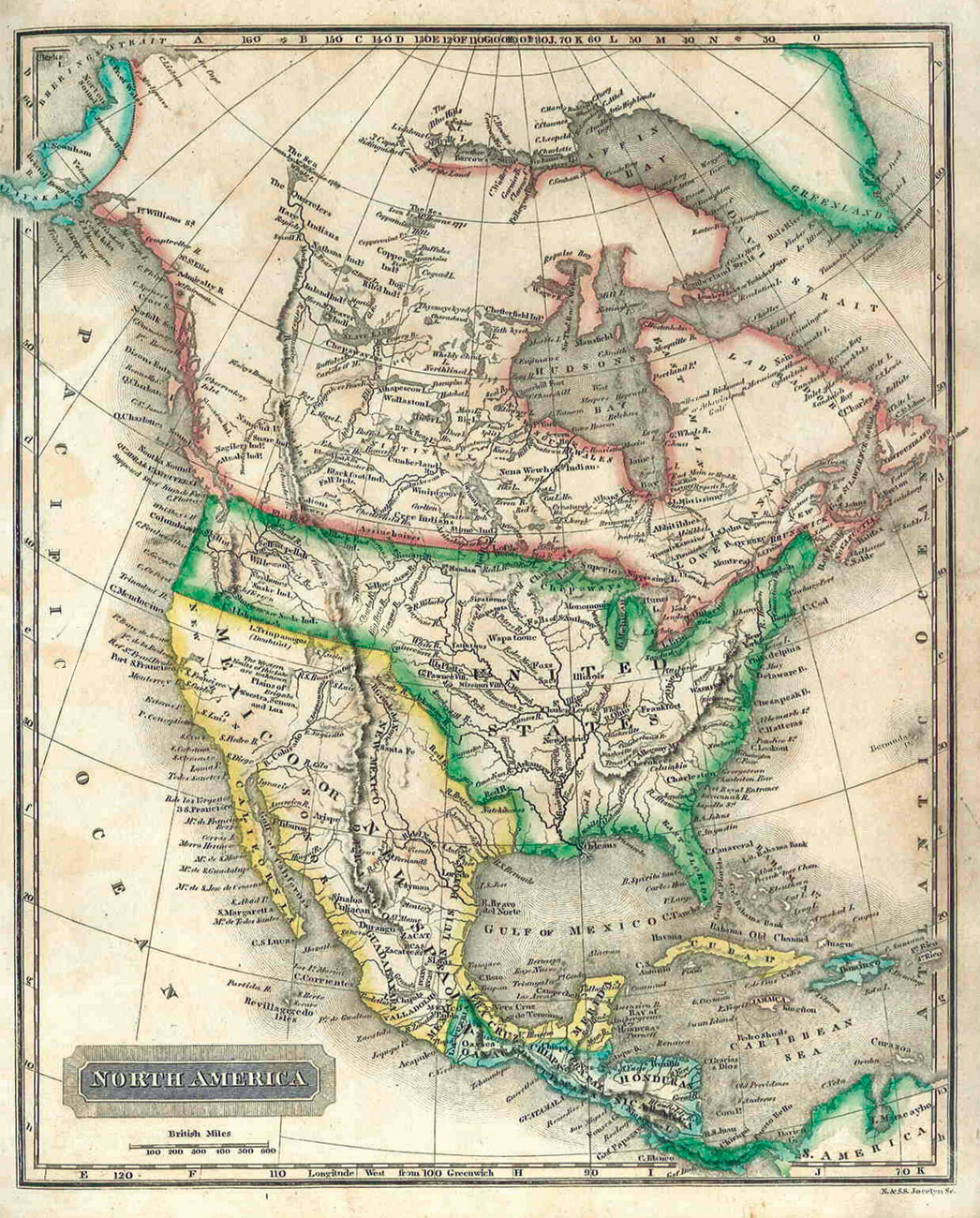

As luck would have it, the Utah Department of Natural Resources Library recently received a very interesting donation—a world atlas from 1826, titled Morse’s New Universal Atlas of the World on an Improved Plan of Alphabetical Indexes, Designed for Academies and Higher Schools, by Sidney E. Morse. The atlas conveys more than just world geography—it visually illustrates what was happening in the early 1800s.

In 1826, as indicated by the map of the United States, Utah was not a state, the Mormon Pioneers had not arrived, Great Salt Lake was not yet named, and the area now known as Salt Lake City was inhabited by the Shoshone, Ute, and Paiute Indian Tribes. However, there is an area on the map designated Valle Salado, which translates from Spanish as Salt Valley, that sits just east of an unnamed lake that most likely represents Great Salt Lake. On the map, the lake is fed by the Buenaventura River to the north, which is now known as the Bear River. The presumed outflow of the lake was represented as a dotted line labeled “Supposed river between the Buenaventura and the Bay of Francisco, which will probably be the communication between the Atlantic and the Pacific.” Around this time, rumors from the Native Americans claimed that the lake did indeed have an outflow, but the entire shoreline had not yet been explored. Jim Bridger, in 1825, was the first white man to reach the shores of Great Salt Lake. In the same year, Jedediah Smith investigated the northern and western edges of the lake, with no success of finding the outflow. The lake was not circumnavigated until 1849 when Howard Stansbury completed the route and officially declared that no river flowed from Great Salt Lake.

Although in 1826 Utah was still 70 years away from statehood, the United States was rapidly expanding its borders from the thirteen original colonies that had gained independence from the British Empire in 1776. As a result of agreements such as the Treaty of Paris in 1783 and the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the continental United States already included roughly three-fourths of the land area that it does today. However, the western-border states were not yet developed and were known as the Missouri and Arkansaw [sic] Territories, as shown on the map of the United States. The area that would eventually become Utah wasconsidered to be part of Mexico and did not become part of the United States until 1848, when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, ending the Mexican-American War.

An example of a better explored area is demonstrated by the map of South America. The map is fascinating because it contains a lot of detail since this area was well explored in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, the entire continent was composed of only seven individual countries (mostly European colonies), and countries like Brazil and Ecuador had only recently become independent from Portugal and Spain, respectively. Changes in Central America, evident from the map of North America, include California joining Mexico, and Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and San Salvador gaining independence from Mexico as the United Provinces of Central America.

During the time in which the atlas was compiled, land was rapidly changing hands as a result of fluctuating European colonial rule. This is reflected in the atlas not only in the level of detail of each individual map, but also by which maps the author chose to include, and the order in which they are presented. For example, there are separate maps of each European country, and each of those contains a high level of detail. In contrast to the European maps, Africa is represented only as a continent, composed of roughly five ambiguous countries, vast blank areas, and terra incognito—parts unknown.

Another interesting fact about the atlas is that the author had some rather famous relatives. Sidney Morse’s father, Jedidiah Morse, both a clergyman and geographer, was given the title “Father of American Geography” for his important role in early American cartography. Sidney’s brother, Samuel F.B. Morse, an artist and inventor, is probably the most well known Morse as a result of his significant contributions in developing the single-wire telegraph and Morse Code. Sidney Morse followed in his father’s footsteps as a geographer as well as an inventor, and The New Universal Atlas is only one of many attributed to him.

Come and see the atlas for yourself! The New Universal Atlas will be on display at the Utah Department of Natural Resources Library until December 2011. The Utah Geological Survey thanks William L. Chenoweth, who has worked with UGS staff as a consultant after retiring from the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, for the donation.

Survey Notes, v. 43 no. 2, May 2011