GeoSights: Tony Grove, Cache County, Utah

by Stephanie Carney

View west-northwest of the Swan Peak Formation (tan and white rocks at base of the cliff) and Fish Haven and Laketown Dolomites.

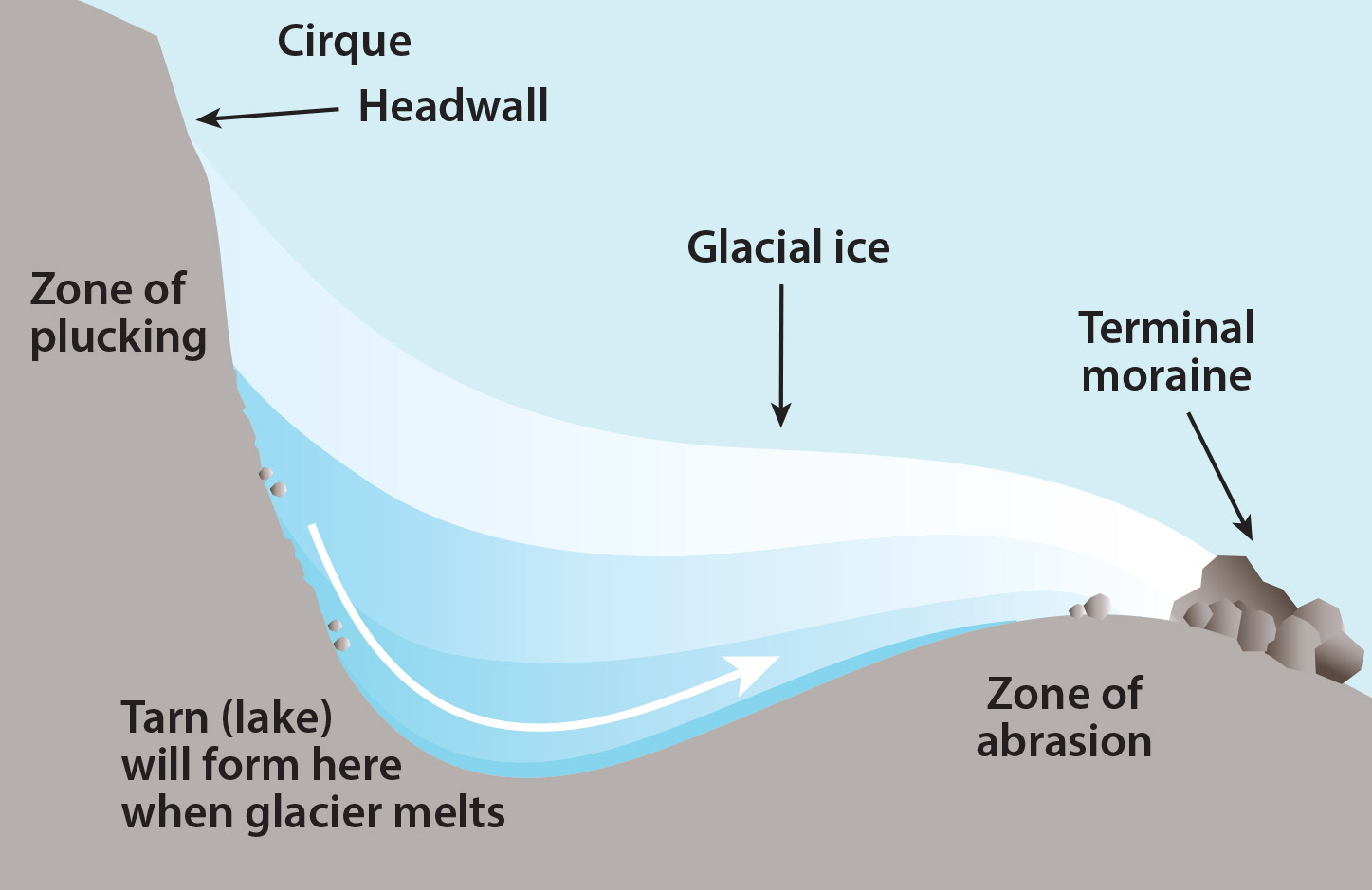

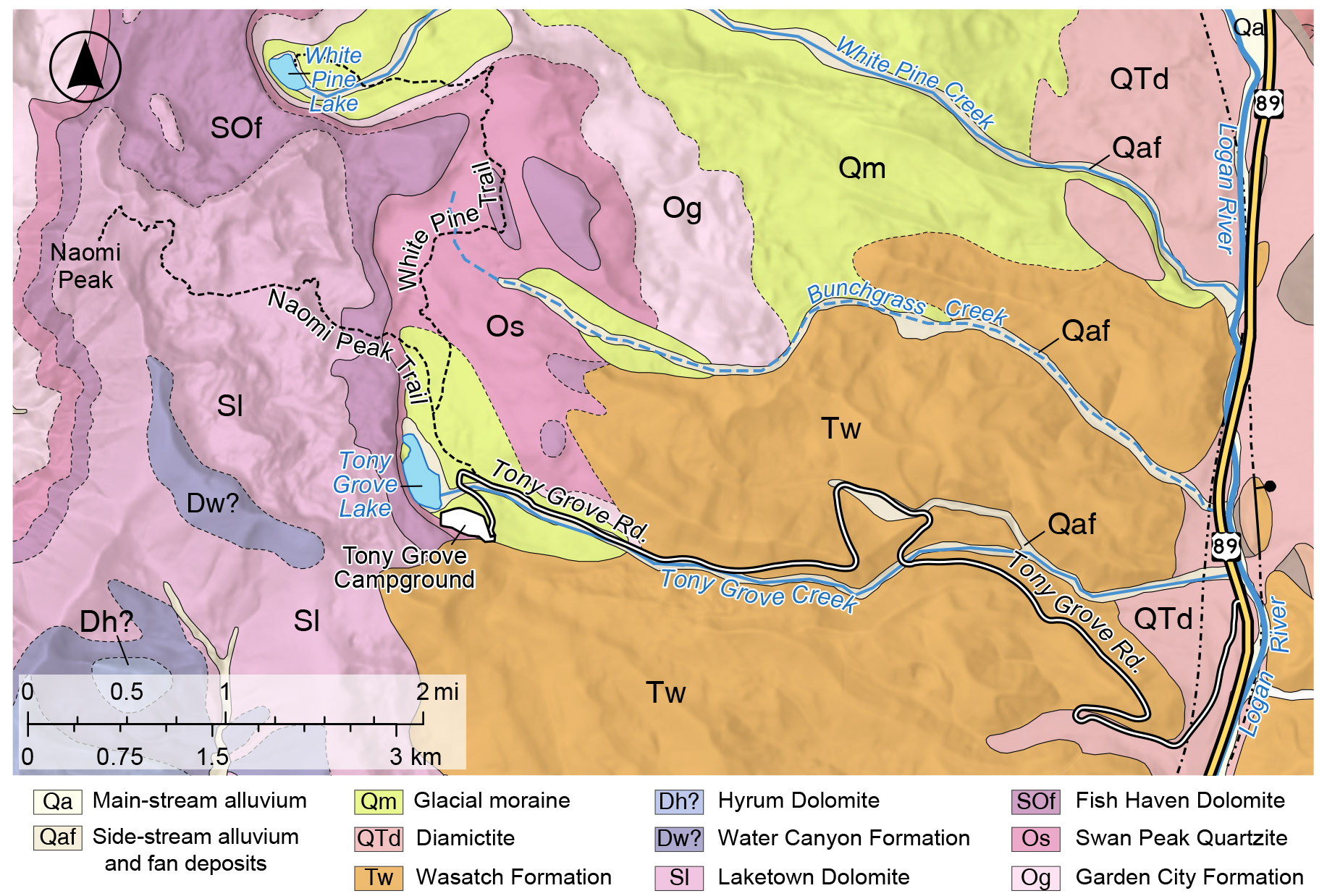

Tony Grove, located in the Bear River Range in northeastern Utah, is a popular area for recreation, including hiking, camping, and paddle-boarding and kayaking on picturesque Tony Grove Lake. This lake and other nearby lakes, such as White Pine Lake, owe their existence to glaciers that once flowed down the drainages of these high elevation areas during the last glacial cycle. The Last Glacial Maximum in northern Utah occurred between about 18,000 to 24,000 years ago, near the end of the Pleistocene Epoch. Through the growth and advancement of these alpine glaciers, the local rocks were scoured and eroded, leaving behind glacial landforms including cirques, glacial moraines (composed of debris or till eroded by the glacier), and hummocky topography. Cirques are alpine valleys shaped like a lopsided bowl or armchair with a steep headwall and a concave floor. After the glacier melts, the floor of the cirque can fill with water to create a cirque lake or tarn, like Tony Grove Lake. The lake is nestled at the base of the cirque’s headwall cliffs and steep slopes, which are composed of Late Ordovician- to Silurian-age (roughly 470 to 420 million years old) Swan Peak Formation, Fish Haven Dolomite, and Laketown Dolomite.

Long before the Bear River Range was subjected to glacial erosion or even existed, the rocks that outcrop at Tony Grove were made from sediments deposited in a tropical marine setting along a passive continental margin, which is a region of minimal tectonic activity much like the present East Coast of the U.S.. Sandstone, siltstone, and shale of the Swan Peak Formation were deposited in a nearshore and intertidal environment, whereas the slightly younger, overlying Fish Haven and Laketown Dolomites were deposited on shallow carbonate platforms like the Bahamas today. After hundreds of millions of years, these sediments, which had been buried and lithified into rock layers, were uplifted and thrust eastward by the Sevier orogeny, a mountain building event during the Late Jurassic through middle Paleogene Periods ( ~160 to 50 million years ago). Near the end of the orogeny, the Eocene-age Wasatch Formation, a reddish-orange-colored conglomerate and siltstone unit, was deposited on top of the exposed older rocks. Beginning around 17 million years ago, the Bear River Range was uplifted further as Basin and Range extension shaped the valleys and mountain ranges seen today.

Today, the Swan Peak Formation is exposed north and west of Tony Grove Lake and it has eroded into an interesting stair-step pattern up the slope from the lake. The unit hosts many trace fossils that were left by burrowing marine organisms, as well as body fossils including trilobites, brachiopods, and nautiloids, which were among the top predators in the ocean during the Ordovician Period. The sandstone beds host conspicuous horizontal trace fossils; although these fossils resemble seaweed-like structures called “fucoids,” they are postulated to indicate offshore burrowing activity of worms and possibly trilobites. Another trace fossil, Skolithos, is also present; these vertical to slightly inclined tubes were made by worms when they needed to escape from strong currents.

Just west of the lake, the Fish Haven Dolomite forms a dark-gray cliff between the white and tan Swan Peak below and the light-gray cliffs of the Laketown Dolomite above. It has abundant reef-forming fossils such as tabulate and rugose (horn) corals, crinoids, and stromatoporoid sponges. The overlying Laketown Dolomite is also known to host similar fossils as well as brachiopods and nautiloids.

The dolomite that forms the Fish Haven and Laketown formations is susceptible to weathering (dissolution) from slightly acidic water. Over thousands of years, slightly acidic groundwater has seeped down into the subsurface through faults and fractures, slowly dissolving the dolomite and creating ever widening pathways (see Survey Notes v. 52, no. 2). This weathering and erosion from water has resulted in the formation of over 100 known caves and pits in the area. The largest cave, Main Drain, is over 1,200 feet deep. These caves are located high above the present water table, and most have formed in a stair-step pattern with shorter horizontal passages connecting longer vertical drops, typical of alpine cave systems. Cave and pit entrances occur on the surface of the Laketown Dolomite, however, entering these caves and pits is not advisable and only professionals with proper equipment should attempt to do so.

Tony Grove has been a recreational destination since the late 1800s. Upscale residents of Cache Valley were known to make the arduous trip up Logan Canyon and camp near the lake during the hot summer months. The name of the lake is thought to come from the word “tony,” a slang term used in the late 1800s and early 1900s to describe the aristocracy or well-to-do. In the 1930s, the lake was augmented with an earthen dam, likely to make it larger and stay reliably filled.

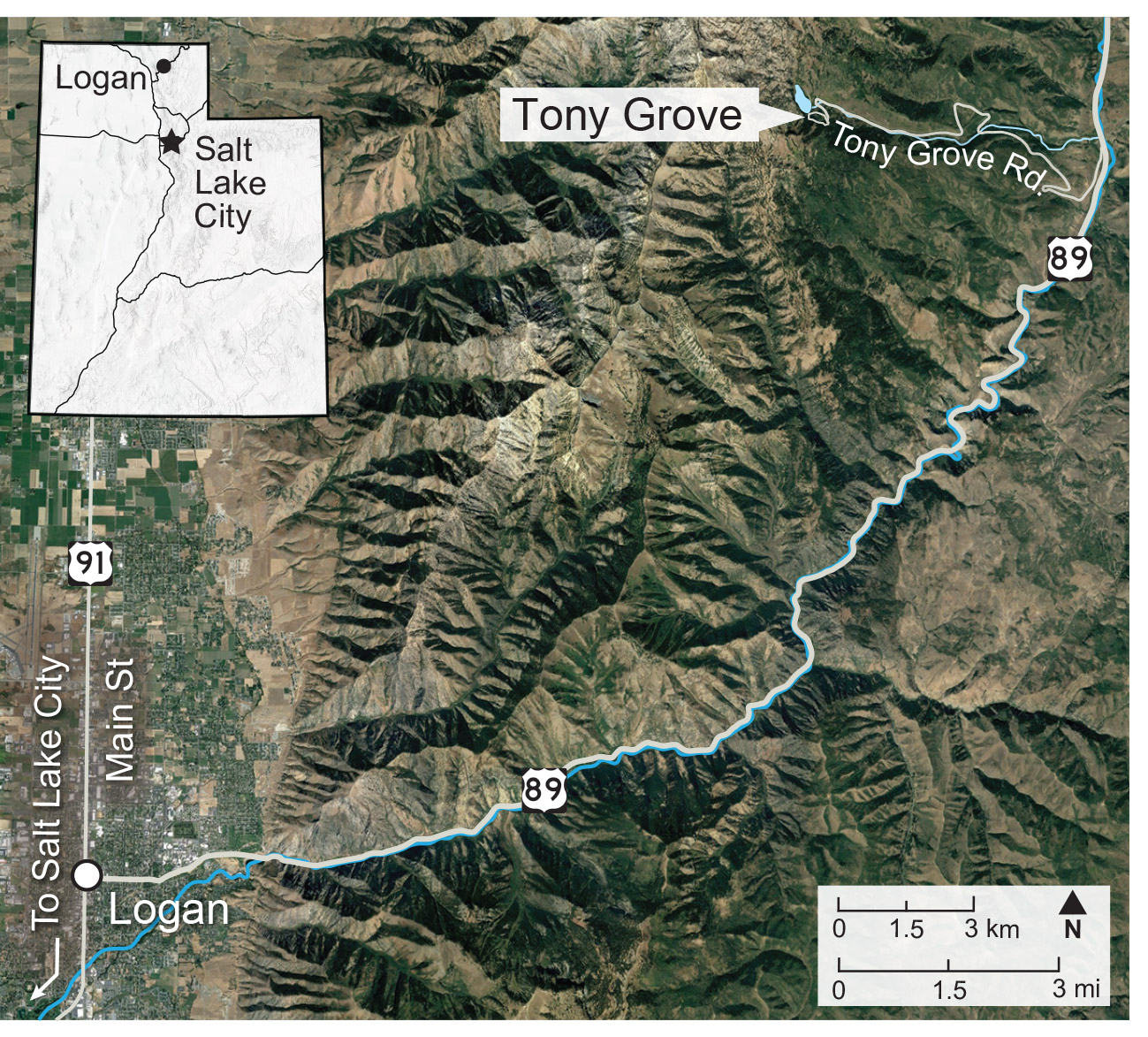

How to Get There

From Main Street in Logan, Utah, head east into Logan Canyon on 400 North/U.S. Route 89 for about 22 miles. Turn left on to Forest Road 141, then take another immediate left onto Forest Road 003. Follow the signs to Tony Grove Lake, which is about 6 miles. Tony Grove Lake is at an elevation of 8,050 feet and its weather (or climate) station records an average of 300 inches of snow in the winter. The road is usually impassible from mid-October to late May, depending on snowfall and temperatures.

Coordinates: 41°53’38.3″N, -111°38’38.3″W