Glad You Asked: What are Moqui marbles?

By Christine Wilkerson

Moqui marbles are small, brownish-black balls composed of iron oxide and sandstone that formed underground when iron minerals precipitated from flowing groundwater. They occur in many places in southern Utah either embedded in or gathered loosely into “puddles” on the ground near outcrops of Jurassic age Navajo Sandstone.

The word Moqui comes from the Hopi Tribe. The Hopi were previously known as the Moqui Indians, named so by the early Spaniards, until their name was officially changed to Hopi in the early 1900s. According to some Internet sources, there is a Hopi legend that the Hopi ancestors’ spirits return to Earth in the evenings to play marble games with these iron balls, and that in the mornings the spirits leave the marbles behind to reassure their relatives that they are happy and content.

Moqui marbles (sometimes spelled Moki) are also known by collectors by many other names—Navajo cherries, Navajo berries, Kayenta berries, Entrada berries, Hopi marbles, Moqui balls, or Shaman stones. Geologists call them iron concretions.

These spherical iron concretions commonly range in size from a fraction of an inch (pea size) to several inches in diameter, although some can be as large as grapefruits. In addition to marbles or balls, iron concretions can be shaped like buttons, pipes, corrugated sheets, UFO “flying saucers,” plates, or doublets and triplets (two or three conjoined balls).

The host rock for the marbles, the Navajo Sandstone, was originally deposited around 180 to 190 million years ago as a huge sand dune field, similar to the modern Sahara, that covered parts of Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, Nevada, and New Mexico. A very thin, microscopic layer of hematite (an iron oxide mineral) coated the sand grains, giving the sand its red color. The sand was later buried by other sediments and eventually cemented into sandstone, during which time the hematite coatings continued to spread over the grains, ultimately giving us some of the most spectacular red sandstones visible in southern Utah.

But not all Navajo Sandstone is red; some Navajo Sandstone is white. While still buried, water containing reducing agents such as weak acids or possibly hydrocarbons (petroleum) traveled slowly through parts of the permeable sandstone, bleaching the red rock by dissolving the iron into the water. This iron-laden water eventually flowed to a place where the groundwater chemistry changed and caused the iron to precipitate. This precipitated iron surrounded and cemented the sand grains and in time formed iron concretions consisting of concentric layers of hard iron minerals enclosing loosely to well-cemented sand. Some recent studies have also proposed that microorganisms later helped convert the precipitated iron into iron oxide.

Once the overlying rock layers were eroded and the Navajo Sandstone revealed, weathering of the sandstone exposed the hard, weather-resistant iron concretions, many of which are amassed in large groups on the surface. Many concretions are located in State Parks, National Parks and Monuments, and Native American reservations where collecting is prohibited.

Martian Blueberries

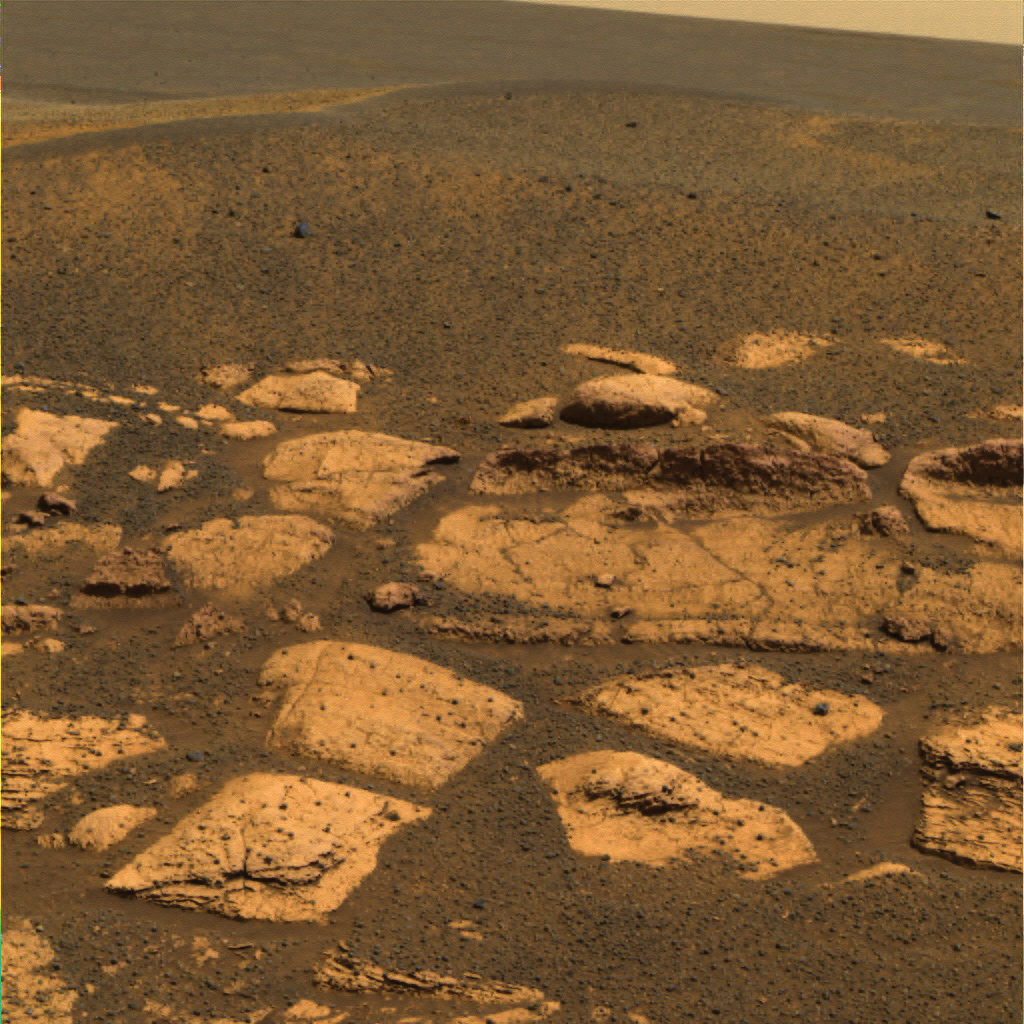

Discovered on Mars by NASA’s Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity in 2004, the Martian blueberries are thought to have formed in a similar manner to the Moqui marbles on Earth, therefore providing some of the first evidence for water in Mars’ ancient past. And just like on Earth, these hematite concretions were found scattered on the ground and embedded in rock outcrops, “like blueberries in a muffin” according to one rover scientist.

Martian blueberries are gray not blue, and are much smaller than most marbles in Utah, usually about BB pellet-size. By continuing to study iron concretions in Utah, geologists can make analogies as to how these blueberries formed on Mars.

Survey Notes, v. 49 no. 3, September 2017