GeoSights: Point of the Mountain, Salt Lake and Utah Counties

By Mark Milligan

Standing at Point of the Mountain today, one might see paragliders, hang gliders, or radio-controlled gliders flying above the valley floor. Standing here 18,000 years ago, one might have heard and seen waves crashing on the shore of Lake Bonneville, glaciers calving into the lake from Little Cottonwood Canyon, and perhaps mammoths, musk oxen, or a saber-toothed cat.

Lake Bonneville was a huge freshwater lake that existed approximately 13,000 to 30,000 years ago. The shorelines left by Lake Bonneville can be seen around Salt Lake and neighboring valleys like rings around a bathtub. Shoreline features include beaches, deltas, wave-cut benches, spits, and bars. The Point of the Mountain spit and adjacent Steep Mountain beach are two of the most spectacular shoreline features in the Bonneville basin.

Geologic Information

The geologic equation for spectacular shorelines at this inland locale includes three parts: a former large lake, a mountain front oriented to receive the onslaught of waves generated by storms approaching from the northwest, and bedrock that is easily pulverized into sand and gravel.

THE LAKE

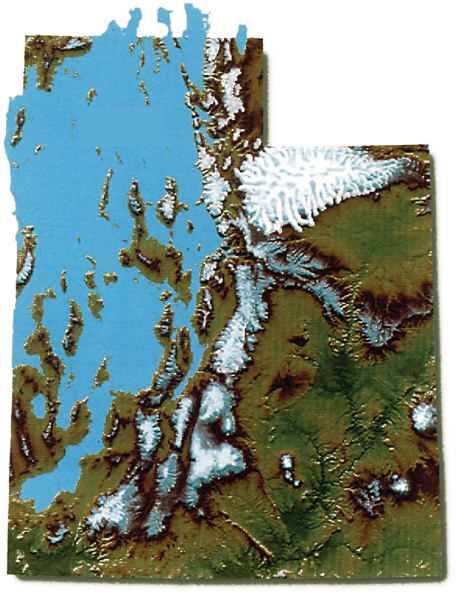

A shift to wetter and colder conditions in the last Ice Age triggered Lake Bonneville’s expansion from the location of the present Great Salt Lake into surrounding valleys. About 18,000 years ago, Lake Bonneville reached its maximum depth of over 1,000 feet and covered about 20,000 square miles. At that time one could have sailed from Point of the Mountain to Idaho, Nevada, or within 30 miles of Cedar City, Utah.

While at its highest level (referred to as the Bonneville shoreline) the lake eroded through a sediment dam at Red Rock Pass in southeastern Idaho and catastrophically dropped over 300 feet to the Provo shoreline. Thereafter, a climatic shift to warmer and drier conditions (similar to present) caused Lake Bonneville to shrink, leaving Great Salt Lake as a salty remnant.

THE MOUNTAIN

The Traverse Mountains are an east-west trending range in an area dominated by north-south trending ranges. They extend between the Wasatch Range to the east and the Oquirrh Mountains to the west, and have a gap cut by the Jordan River. Additionally the Traverse Mountains lie at the boundary between two independent segments of the Wasatch fault, the Salt Lake City segment to the north and the Provo segment to the south.

The location and orientation of the Traverse Mountains is thought to be due to an ancient crustal structure that predates the crustal extension that created the modern landscape. The east-west orientation of these mountains subjected their north flank to intense waves generated across a long and unimpeded stretch of Lake Bonneville that once extended to the north.

THE ROCK

The north-facing Steep Mountain part of the Traverse Mountains is composed of highly fractured and weakened quartz sandstone (quartzite) of the roughly 300-millionyear- old Oquirrh Group. This quartzite was readily pulverized by waves, creating an enormous supply of sand and gravel. Some of this sand and gravel remains on the Steep Mountain beach, but strong longshore currents traveling west and south through the Jordan River Narrows transported most of the material, redepositing it in the Point of the Mountain spit.

A spit is defined as a ridge or embankment of sediment attached to the shoreline at one end and terminating in open water at the other. The Point of the Mountain spit is a complex feature with various Lake Bonneville-age embankments that are underlain by sediments deposited by lakes that pre-dated Lake Bonneville and even older bedrock.

How to Get There

GeoSights – Point of the Mountain location map.

Point of the Mountain can be readily seen from I-15 where it marks the boundary of Utah County to the south and Salt Lake County to the north.

For a closer view, the top of the spit can be reached from either county. However, the top of the spit is dissected by a large gravel quarry and can no longer be traversed.

To access the north side from Salt Lake County: Take I-15 south to exit 289 for UT-154/Bangerter Highway. Go left (east) at the fork and continue on Bangerter Highway (which becomes South Bangerter Parkway and then Traverse Ridge Road) for approximately 2.4 miles, then turn right onto Steep Mountain Drive. Continue for 1.4 miles to Flight Park North.

To access the south side from Utah County: Take I-15 north to exit 284 for UT-92 towards Highland/Alpine. Turn right (east) at the end of the off-ramp. After approximately 100 yards turn left onto Digital Drive (Frontage Road) and travel north for 2.1 miles to Flight Park Road. Turn right and continue 1.5 miles up to the Flight Park State Recreation Area.

Please stay well away from the sand and gravel pits. Pit high walls are indeed very high and may be unstable.

Survey Notes, v. 48 no. 2, May 2016