Energy News: The Benefits of Oil and Gas Production to the State of Utah and Its Citizens—How Things Work!

By Thomas C. Chidsey, Jr.

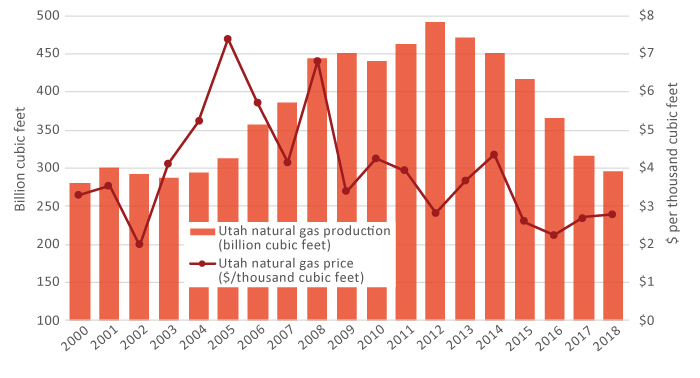

Over the past decade, Utah has consistently ranked about 10th and 13th in domestic oil and gas production, respectively, in spite of the price collapses that began in 2014. In 2018, over 36 million barrels of oil and 295 billion cubic feet of gas was produced from more than 11,000 wells in Utah. Revenue to Utah and its citizens from oil and gas production varies depending on market prices, land ownership, and the amount produced. A decrease in prices results in less drilling activity and thus a decrease in production. In addition, as oil and gas fields mature, production naturally decreases along with revenue.

Land Ownership

About two-thirds (67 percent) of the lands in Utah are owned by the federal government including National Parks, National Monuments, National Recreation Areas, National Historical Sites, National Forests, Military Reservations, and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Other lands in Utah are owned by Native American tribes, the State (including State Parks, Sovereign Lands [the beds of major waterways and lakes, for example the Green and Colorado Rivers, and Great Salt Lake], and School Trust Lands), and private entities (ranches, farms, etc.). The School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration (SITLA) is an independent state agency that manages 4.5 million acres of Utah lands, of which over 1 million acres are currently leased for oil and gas exploration for the exclusive benefit of Utah’s schools and 11 other beneficiaries. Most of Utah’s oil and gas production comes from BLM and tribal lands in the Uinta and Paradox Basins of eastern and southeastern Utah, respectively.

Oil and Gas Royalties

Oil and gas royalties are the cash value paid by a lessee (usually an oil company) to a lessor (the landowner or whoever has acquired possession of the royalty rights) based on a percentage of gross production from the property, free and clear of all costs. Currently, the federal government charges a royalty of 12.5 to 19.6 percent for oil and 9.2 to 12.5 percent for gas extracted from public lands (based on the composition, quality, etc. of the produced crude oil and gas); some royalty agreements with other landowners may be as high as 25 percent. After an oil company discovers oil or gas on federal (or state or private) lands, subsequent wells are drilled to develop and produce the resource. Once production starts, royalties begin to be paid to the landowner(s). For example, if a new well produces 100 barrels of oil per day, and the current market price is $50 per barrel that particular month, then the cash flow would be 100 x $50 or $5,000 per day. The landowner (such as the BLM), who requires a 12.5 percent royalty payment on that production, would receive $625 per day ($5,000 x 0.125).

A question often asked: “Does Utah and its citizens get anything out of oil and gas production on federal lands?” The answer is an emphatic yes! Forty-two to forty-five percent of the royalty payment from oil and gas production (as well as coal, industrial minerals, gilsonite, geothermal, etc.) on federal lands comprise what are called Mineral Lease disbursements and are divided up among several state agencies and counties. For example, the Utah Department of Transportation receives 40 percent of the royalty, a number of counties split 32 percent, and the rest goes to other state entities including the

Utah Geological Survey (UGS). In the example discussed above, Utah would receive $262.50 (42 percent) per day from that one hypothetical well. As total oil and gas production and prices fluctuate, so does the royalty revenue to Utah, ranging from as much as $155 million when oil was over $112 per barrel in 2011 to $64 million when oil dropped to a low of $29 per barrel in 2016. The UGS receives 2.25 percent of the state’s part of this payment, which amounts to one-fifth (20 percent) of the UGS’s annual budget and thus is a critical source of funding that is often difficult to predict. Utah schools received about $28.7 million from oil and gas activities on SITLA lands for the 2018 fiscal year. Like many states, Utah also charges a severance tax (3 to 5 percent; $9 million in 2017) and a conservation fee (0.2 percent; $3.3 million in 2017) based on the value of the oil and gas produced and saved, sold, or transported from the field where it is produced. Finally, Utah charges property taxes on oil and gas facilities; this amounted to $47 million in 2017.

Tax collections on oil and gas production and activities in Utah, and total Mineral Lease disbursements, 2000-2017. Data from Utah State Tax Commission.

Some may remember the old 1960s TV comedy The Beverly Hillbillies. Royalty payments turned the poor mountaineer, Jed Clampett, into a millionaire when “black gold” was discovered on his land! In reality, royalty payments to private landowners can be very large or very small and especially complicated. The mineral rights under a ranch or farm, for example, may be divided up (and not always equally) among multiple family members or heirs several generations removed from the property; all are entitled to monthly royalty checks. Wells may produce for 30 years or longer. In addition, many old oil wells are often classified as stripper wells, producing 15 barrels or less per day. Yet royalty payments will continue to be paid to those owners as long as the wells produce. Ten barrels per day x $50 per barrel x 12.5 percent royalty = $62.50 per day. Divide that up among perhaps dozens of people entitled to a share of the royalty and few will be moving to Beverly Hills. Throw in the variations in oil and gas prices as well as changes in production, and oil companies often have to employ large numbers of accountants to handle the monthly royalty payments from hundreds of wells.

Leasing and Subsurface Mineral Rights

Before an oil company drills a well, it must first lease the land from the owner of the subsurface mineral rights. Leasing is usually done after extensive geologic, geophysical, and economic evaluations of an area—subsurface mapping, acquiring seismic data, analyzing cores and well logs, determining the hydrocarbon source and reservoir rocks, estimating dry hole risks and resource potential, and the costs associated with its development (exploration programs, drilling, production wells, and infrastructure such as pipelines). Acquired leases owned by the federal and state government are often obtained through a bidding process. The price per acre varies from less than $10 to $1,000s depending on whether or not the land is within a relatively inactive area, a “hot” new exploration play, or if oil and gas prices are high or low; these monies are also a source of revenue for the federal and state governments. The company may hold on to the lease anywhere from three to ten years after which it goes back to the landowner and can be offered again to interested companies. If production is achieved, the company retains the lease as long as their wells produce (referred to as a lease “held by production,” i.e., HBP). Companies usually try to acquire large blocks of leased acreage to cover their drilling prospects although some pick up small leases just to be “part of the action.” Finally, companies sometimes reduce their risk by forming units or “farming out” a share of their leases and drilling costs with other companies while retaining an interest in any production that may occur.

Covenant oil field, east of Richfield, Sevier County, Utah. The subsurface mineral rights in the field are owned by the BLM, SITLA, and a private entity.

Private landowners lease the mineral right under their lands differently than the federal and state governments. Typically, landowners are approached by the oil company or its hired representative, called a landman, who may make a monetary offer, called a “Bonus,” to lease the mineral rights. The price per acre and duration of the lease are usually similar to those owned by the state and federal government; however, small leases may receive smaller offers because companies usually try to tie up larger lease blocks of acreage. As is most often the case, oil and gas are not found under a property, and the only money that the landowner receives will be that from leasing the mineral rights. If oil or gas is discovered under a lease, even a small one, the mineral owner is still entitled to their proportional share (royalty) of the estimated resource being “drained” under the land no matter if a well is actually on the surface of the property or not. Finally, some landowners may not be aware of what mineral rights they own or do not own. They may own all or a portion of the subsurface mineral rights, or if they only own the surface rights, then they get nothing from leasing or production. This situation may occur if previous landowners sold the surface property (a farm or ranch, for example) but retained the subsurface mineral rights, or sold a percentage of the rights to a third party—all independently of how many times the surface ownership changes hands over the years. For example, a farmer may own a 640-acre section (1 square mile) of land but they own the mineral rights to only 320 acres at 100 percent and 40 acres under another part at 50 percent with all remaining mineral rights owned by someone else. However, the surface landowner still has rights even if they do not own the subsurface mineral rights, especially if the oil company conducts exploration or development activities on their land, such as shooting seismic lines, drilling, or building pipelines. The landowner can negotiate reasonable “damage” fees for these activities. For instance, when shooting a seismic line, shallow-depth shot holes may be drilled in an area of interest. Explosive charges are set off in shot holes that create seismic waves, which bounce off the subsurface layers of rock to give a better picture of the geologic structure below. The landowner may receive $300 to $500 in damage fees per hole.

If a landowner is unsure of the mineral rights, the local county clerk’s office can usually help. When contacted by a landman representing an oil company about leasing the mineral rights, a landowner should consider hiring an attorney who specializes in oil and gas leasing. In addition, numerous websites are available with helpful information, advice, and negotiating guidance on leasing. Landowners may also want to know about the geology of their land especially pertaining to oil and gas. Although the UGS cannot specifically evaluate individual properties (hired geologic consultants can, however), we can answer general questions and recommend our numerous publications on oil and gas resources, plays, etc. (see Public Information Series 71, “Utah Oil and Gas,” and Bulletin 137, “Major Oil Plays in Utah and Vicinity,” for example) that are available for free from our website.

Oil and Gas Revenue—The Bottom Line

Revenue from oil and gas production and leasing can be a double-edged sword to Utah and its citizens. When prices are high, the state has more funds for education, roads, and other services. At the same time, high oil prices affect the gas pump. When prices are low, the revenue and its benefits to the state consequentially fall but it becomes cheaper to fill up our vehicles. Ultimately, however, the fact that Utah is rich in oil and gas resources is of great benefit to the state and its citizens, now and well into the future.